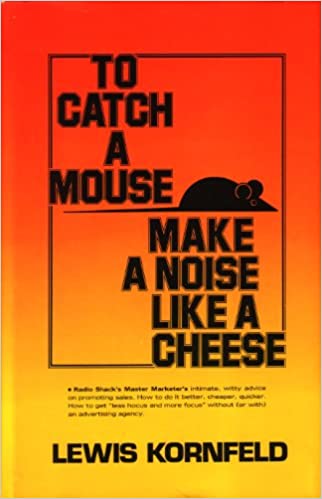

by Lewis Kornfeld (1983)  I purchased this book at the Montana Valley Book Store in Alberton, Montana, USA. The village (population 452) is a friendly place with few businesses outside of this one large used bookstore. The experience immediately reminded me of Hobart, New York. Hobart is a hidden gem home to less than 500 people but supports 5 bookstores. When I asked about the stacks of IBM punch cards I saw laying around Hobart, one store keeper opined that it’s because the old IBMers living in the area keep the local book business going.

I purchased this book at the Montana Valley Book Store in Alberton, Montana, USA. The village (population 452) is a friendly place with few businesses outside of this one large used bookstore. The experience immediately reminded me of Hobart, New York. Hobart is a hidden gem home to less than 500 people but supports 5 bookstores. When I asked about the stacks of IBM punch cards I saw laying around Hobart, one store keeper opined that it’s because the old IBMers living in the area keep the local book business going.  Montana Valley Book Store David Schmudde (2022)

Montana Valley Book Store David Schmudde (2022)

The Adman Who Launched 1,000 Computers When No One Else Could

The Product

Lewis Kornfeld was an adman turned electronics executive at Radio Shack. His time as the company’s president from 1970-1981 was an era of tremendous growth. This period saw the introduction of two significant consumer hits for Radio Shack: citizens band radio and the TRS-80 personal computer. The TRS-80, announced on August 3, 1977 at New York’s Hotel Warwick,Kornfeld, Lewis. To Catch a Mouse Make a Noise like a Cheese. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, 1983. 269.

cemented Radio Shack as a force in early personal computing.BYTE offers contemporaneous coverage in The TRS-80: Radio Shack’s New Entry (Vol 2 No 11, Nov. 1977, pg 446): “Announced in August, the new Radio Shack TRS-80 is a major entry into the personal computer market. The $599 single board Z-80 based unit comes complete with a full ASCII character set keyboard, cassette recorder and video display monitor. Also included for the price is 4 K bytes of pro- grammable memory and 4 K bytes of read only memory; the latter features a built-in BASIC package.”

To Catch a Mouse Make a Noise Like a Cheese was an opportunity for Kornfeld to lay claim to this success. He asserts his claim to TRS-80 fatherhood in at least three different places.Kornfeld, Lewis. To Catch a Mouse Make a Noise like a Cheese. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, 1983. 61, 262, 330.

[Radio Shack’s] TRS-80 personal computer (for which I get fathership credit because when the buck stopped on my desk in 1976 I said “BUILD”)

And it was your claimant correspondent who authorized the design and manufacture of the TRS-80 Model I, and selected its nomenclature, general appearance and first system selling price, even if reconstructed history evokes different claims for different names as time goes by (as created by newer pressures on business journalism).

Having named, defined and marketed the world’s first mass-produced personal computer, the TRS-80 Model I, it was enough, I thought erroneously, to settle for pointing the way and blessing the voyage.

Being first on retail shelves nationwide puts Radio Shack in pole position ahead of Jack Tramiel, Chuck Peddle, and the folks at Commodore,Commodore’s computer actually appeared a month before the TRS-80 in BYTE. From Commodore’s New PET Computer (Vol 2 No 10, Oct. 1977, p.50): “The price of the PET is $595 complete with 4 K bytes of programmable memory. The $795 version features 8 K bytes of programmable memory. All IO connections (excluding the built-in tape drive, keyboard and video display) are made via an IEEE- 488 bus. The PET is an excellent example of the true appliance computer: a neat, self-con- tained graphics oriented package designed for the mass market as well as for the serious experimenter.”

Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and the folks at Apple, and William Lowe, Don Estridge, and the folks at IBM. It must be remembered that no one knew exactly what a mass market consumer would do with a personal computer in 1977. Consider the problem from Kornfeld’s perspective: “There were no known customers asking for [a personal computer]” therefore “it was impossible to identify typical buyers.”Apple’s 1978 Prospectus struggled to identify any uses to entice investment and pick up their 3rd-rate sales. You might buy an Apple II to make “better financial decisions,” enjoy “increased leisure time,” and have “complete security of personal information” with “increased personal comfort.”

Its difficult to imagine now, but taking up valuable retail shelf space was a big risk.

Kornfeld rolled the dice in spite of the unknowns. “We had no opening order quantity set beyond what would be needed to buy parts economically, but not less than 1000 were being considered […] and since all we had was a very rough idea of parts and labor costs, a selling price had yet to be firmed up”Kornfeld, Lewis. To Catch a Mouse Make a Noise like a Cheese. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, 1983. 268.

Wherever Kornfeld’s place is in computer history, the benefit of having an adman steering the ship is pretty clear. Radio Shack sold a lot more computers than their contemporaries in the early days. The TRS-80 quickly became the best-selling personal computer and Radio Shack enjoyed a prime spot in computer sales throughout the 1980s.

The Technique

The book’s style is filled with folksy wisdom and clever turns of phrase. So much so that it’s actually quite difficult to read. Kornfeld’s view on computing is dry but his view on advertising is particularly colorful. Take the following example:Kornfeld, Lewis. To Catch a Mouse Make a Noise like a Cheese. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, 1983. 256.

A commodity is a product whose retail value is reduced to its lowest common denominator by having its value known and agreed on and changed at the whim of the Market. To make your product a product instead of a commodity, ADD VALUE to it, and CHARGE FULLY for the value added. It must be a reflex at Gucci.

The wisdom of Kornfeld’s thought is apparent without the Gucci quip. While the reference adds color, too many of the references evaded my grasp and only distracted.

Kornfeld’s 65 rules of marketing are practical but they don’t really offer much insight. For example, number 4: “One of the quickest ways of learning what to do in any business situation is first to be able to observe it done correctly.” Number 63: “When opportunity knocks in an unusually loud manner, tear a hole in the wall and make it a second door.” On the other hand, his consistent skepticism of Madison Ave. admen is generally instructive.

The book contains approaches to marketing that transcends its era, but the book itself is not timeless. The most interesting aspects of To Catch a Mouse Make a Noise Like a Cheese concern the TRS-80 while Kornfeld’s other big hit, the CB Radio, is barely mentioned. Most of the book’s limitations are imposed by the style of the author. While I’m always happy to read someone with a distinct approach to writing, the weight of Kornfeld’s pen is a bit too heavy for my liking.