Several years ago, I got frustrated with updating my resume, my curriculum vitae, and my website every time something happened in my professional life. I decided to move all the information into generic data structures and wrote a program to generate all the requisite outputs - various resume formats, different webpages, etc….

My current job search motivated me to finally wrangle a problem that I had been putting off for a while - properly recording and displaying dates. This may sound trivial, but dates present a number of tricky edge cases. They need to be displayed in different formats in different contexts, spans of time need to be calculated, and there are inconsistencies in how they are recorded.

I want to document the most precise time and date available about a professional event in a format that is:

- Easy to write and read: add and update events in a plain text file

- Easy to format: automatically change a date’s display depending on context, calculate and display a span of time, etc…

Non-programmers probably haven’t thought about the problem of recording time on a computer since the Y2K Bug. Storing Time part 1 and part 2 will cover some of the conceptual challenges dealing with storing memory and time on a machine while also including code snippets. I’ll be using Java Time and Clojure to read and write time from an .edn file.edn is an extensible data notation used to convey values. It is often used where one might use JSON, but it offers several advantages. More at the official edn readme.

Even if that means little to you, I think these blog entries cover concepts of general interest.

Not All Time is Equal

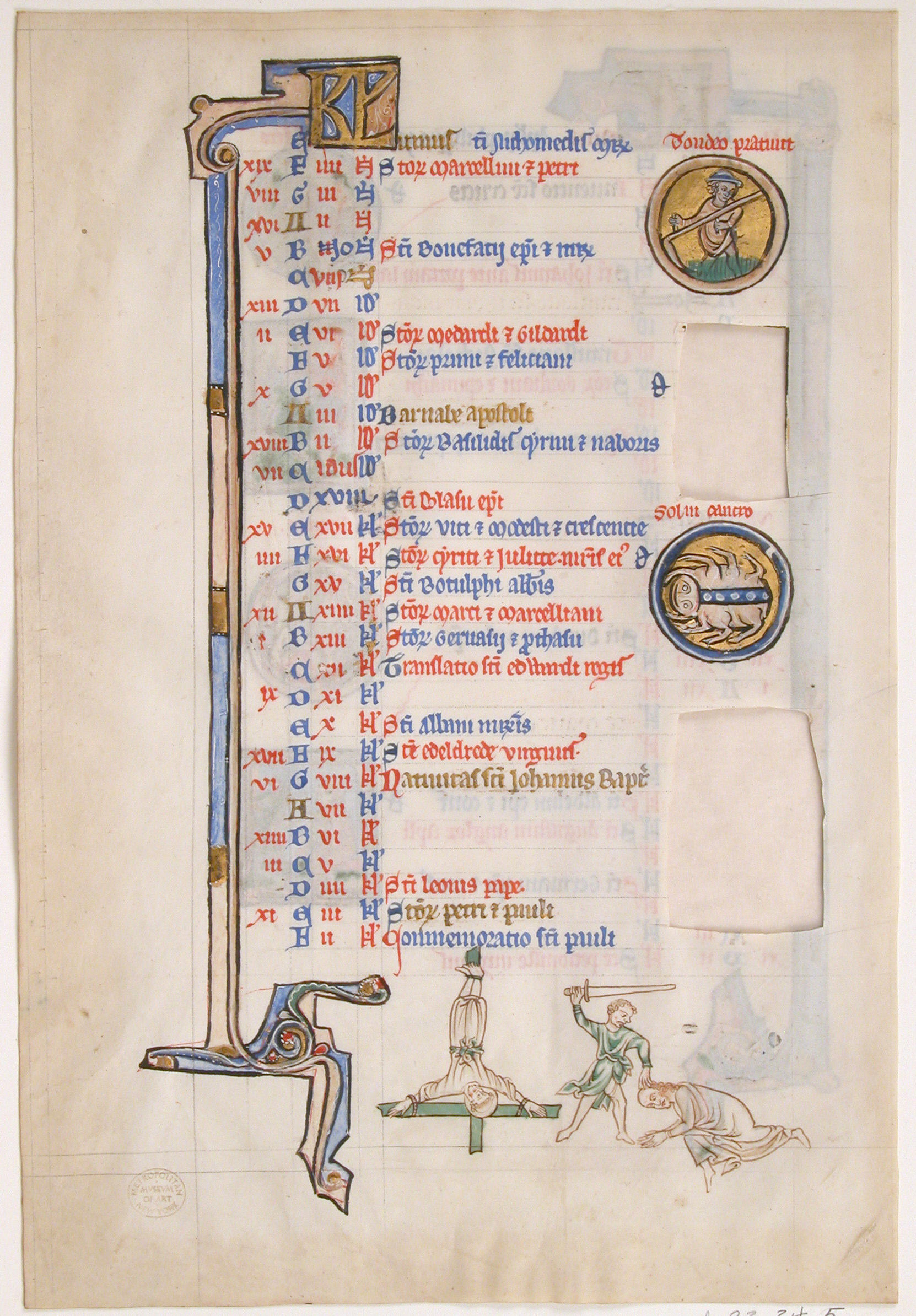

“This manuscript page from a psalter uses the same format as calendar pages found in a typical book of hours. June is written at the top; the text includes the names of saints and feasts to be celebrated during that month.” “Manuscript Leaf With June Calendar, From A Royal Psalter”. The Metropolitan Museum Of Art, 13th century.

“This manuscript page from a psalter uses the same format as calendar pages found in a typical book of hours. June is written at the top; the text includes the names of saints and feasts to be celebrated during that month.” “Manuscript Leaf With June Calendar, From A Royal Psalter”. The Metropolitan Museum Of Art, 13th century.

Java Time and Joda Time are the workhorses of countless computer systems around the world. Travel reservations, bank transfers, employee databases - any system that has a time component must deal with basic problems like months and years of different lengths and locations in different time zones. And while most programmers agree that Java/Joda Time works well enough, the abstraction leaves something to be desired.

Take something simple like adding a month to a date. The results may be surprising. According to Java Time:

- March 15, 2015 plus one month is April 15, 2015.

- March 30, 2015 plus one month is April 30, 2015.

- March 31, 2015 plus one month is April 30, 2015.

Here is the same logic, written and run in Clojure:These results rely on the plusMonths method that works on a Java Time LocalDate object. I’ll go into detail later. For the curious, here is the function I’m using: (defn add-1-month [date] (-> (java.time.LocalDate/parse date) (.plusMonths 1) str)).

(add-1-month "2015-03-15")⇒"2015-04-15"(add-1-month "2015-03-30")⇒"2015-04-30"(add-1-month "2015-03-31")⇒"2015-04-30"

It both makes sense and feels incorrect. In part because Java uses methods called plusMonths and plusDays and we expect addition to be associative: (2 + 3) + 4 = 2 + (3 + 4).

Adding a day and then adding a month should be the same as adding a month and then adding a day.Again, I will go into detail about this later, but if you’re curious, here is the add-1-day function: (defn add-1-day [date] (-> (java.time.LocalDate/parse date) (.plusDays 1) str))

But it’s not always true. Take the example of May 30th:

(add-1-month (add-1-day "2015-03-30"))⇒"2015-04-30"(add-1-day (add-1-month "2015-03-30"))⇒"2015-05-01"

Other Ways of Modeling Time

Eric Evans addresses the nuance of time math in his talk Modelling Time. He suggests that arithmetic is the wrong abstraction. Evans describes taking inspiration from Clojure, a list processing language at heart, to develop a different abstraction.

- Time is a list of units. So July holds a list of days

July 1, July 2, ... July 31. - Intervals are where sequences meet.

July 1meetsJuly 2.JulymeetsAugust.2020meets2021(if we’re lucky). So determining the size of the interval is a matter of counting the number of items in a list that exist in between.

Evans’ model includes an implementation of Allen’s interval algebra that is beyond the scope of this post. Suffice to say, Java Time is incredibly popular, but there are other approaches that may be more accurate and less complex.

Even something like a regular sequence of intervals - like the tick of the clock - can be unintuitive. In Date and Time are more difficult than you think, Alex Bolboaca and Adrian Bolboaca discuss time zones, the international date line, and relativistic time.

Relativistic time is a real mind-bender with practical consequences. For example, engineers must take into account the speed of orbiting satellites and the curvature of spacetime when estimating GPS coordinates. To stay in lock-step with clocks on the Earth’s surface, satellite clocks must tick 38 microseconds faster in aggregate every day. Errors in time-keeping can lead to kilometer-sized positioning mistakes that get worse over time. The GPS on your phone would be worthless if these computer clocks did not observe the rules of Einstein’s theory of relativity and run at different speeds.

The Basics of Java Time (in Clojure)

Coming back to Earth and dealing within the confines of my own lifetime is enough of a challenge for today. Even with its imperfections, Java Time’s ubiquity and familiarity make it a sensible choice for my project.This section is also available as a runnable notebook on Nextjournal. The notebook includes more detailed information about Java Time and Joda Time in Clojure.

The easiest way to work with Java Time across Clojure and edn is Henry Widd’s cljc.java-time.Along with his time-literals library, Widd provides a way to seamlessly move time data from ClojureScript ↔︎ Clojure ↔︎ edn (or any other serialized transmission/storage). This will be important in Part 2 of Storing Time.

Widd dives into the details of Java Time in his talk Cross Platform DateTime Awesomeness at Clojure/north 2019. Here are a few Java Time/cljc.java-time basics.

Require cljc.java-time and parse a string of numbers formatted as a date:

(require '[cljc.java-time.local-date :as ld])

(ld/parse "2015-02-12")⇒ [java.time.LocalDate, "0x59cd2839", "2015-02-12"]

Turning the string into a java.time.LocalDate object makes them easy to manipulate. Add 90 days to 2015-02-12:

(defn add-90-days [date]

(-> (ld/parse date)

(ld/plus-days 90)

str))

(add-90-days "2015-02-12")⇒ "2015-05-13"

Getting today’s year is straight forward, (ld/get-year (ld/now)) ⇒ 2020. But getting today’s day of the week requires a little more work because date operations can return many different types.

(ld/get-year (ld/now))returns ajava.lang.Integerld/nowreturns ajava.time.LocalDateld/get-day-of-weekreturns ajava.time.DayOfWeek

Getting the object with the name of today’s day of the week:

(ld/get-day-of-week (ld/now))

⇒ [java.time.DayOfWeek, "0x3555cd3d", "SUNDAY"]

But working with "SUNDAY" as a string requires a component of the cljc.java-time library that can deal with the java.time.DayOfWeek Enum type:

(require '[cljc.java-time.day-of-week :as dow])

(dow/to-string (ld/get-day-of-week (ld/now)))⇒ "SUNDAY"

Those are the basics of working with Java Time. Part 2 details the nuances of storing and reading timestamps in an edn text document while also considering the larger questions of digital memory, information, and archaeology.