I had the distinct privilege of presenting at the Polytechnic University of Turin’s Nexa Center for Internet & Society last Wednesday. The talk, subtitled Preservation is a Verb, explored the problem of preserving immaterial art and argued that documentation does not suffice. Preservationists must think about art as the result of interactions in a complex system (a verb) rather than an object or an entity (a noun).

Philip Agre crystallized this for me in his book, Computation and Human Experience (1997). Agre suggests that the 20th century efforts in artificial intelligence were stuck in a mentalist model. The actual interaction between an individual and an “outside world” (the environment) is a marginal concern in this approach (70). This approach suggests that most of the important work happens within the mind - or a model of them mind in artificial intelligence.

The mentalist conception also saw ascendancy in the Object Oriented Programming (OOP) craze that took hold in the 1990s. As it was practiced, OOP focused on building good models, known as objects, that would eventually interact.

Agre sought to place the interaction front-and-center, “Individual and environment are still understood as different things, but it becomes impossible to understand them except as participants in a third figurative ‘thing,’ namely the interaction itself” (71). This is the interactionist approach that Agre argues for.

The “third figurative thing” is actually what we want to preserve in networked art. This phenomenon is probably best depicted in MTAA’s Simple Net Art Diagram from 1997.

MTAA Simple Net Art Diagram (1997)

MTAA Simple Net Art Diagram (1997)

The historical context that Agre provides for his claim ties into the history of art:

The concept of describing human life using metaphors of interaction is, of course, hardly new. After all, one of the lines of computational research that symbolic AI largely displaced in the 1960s - cybernetics - employs a particular set of qualitatively limited but mathematically complex interactionist technical schemata (71).

Cybernetics, Cyberspace, and Art

Art which has explicitly transcended a material state has taken many names: Anti-Form Movement, Process Art, Systems Aesthetic, Systemic Art, Conceptual Art, and Cybernetic Art. Two art exhibitions, Cybernetic Serendipity (London 1968) and Les Immatériaux (Paris 1985), focus their attention on such artworks.

Gordon Pask The Colloquy of Mobiles (1968)

Gordon Pask The Colloquy of Mobiles (1968)

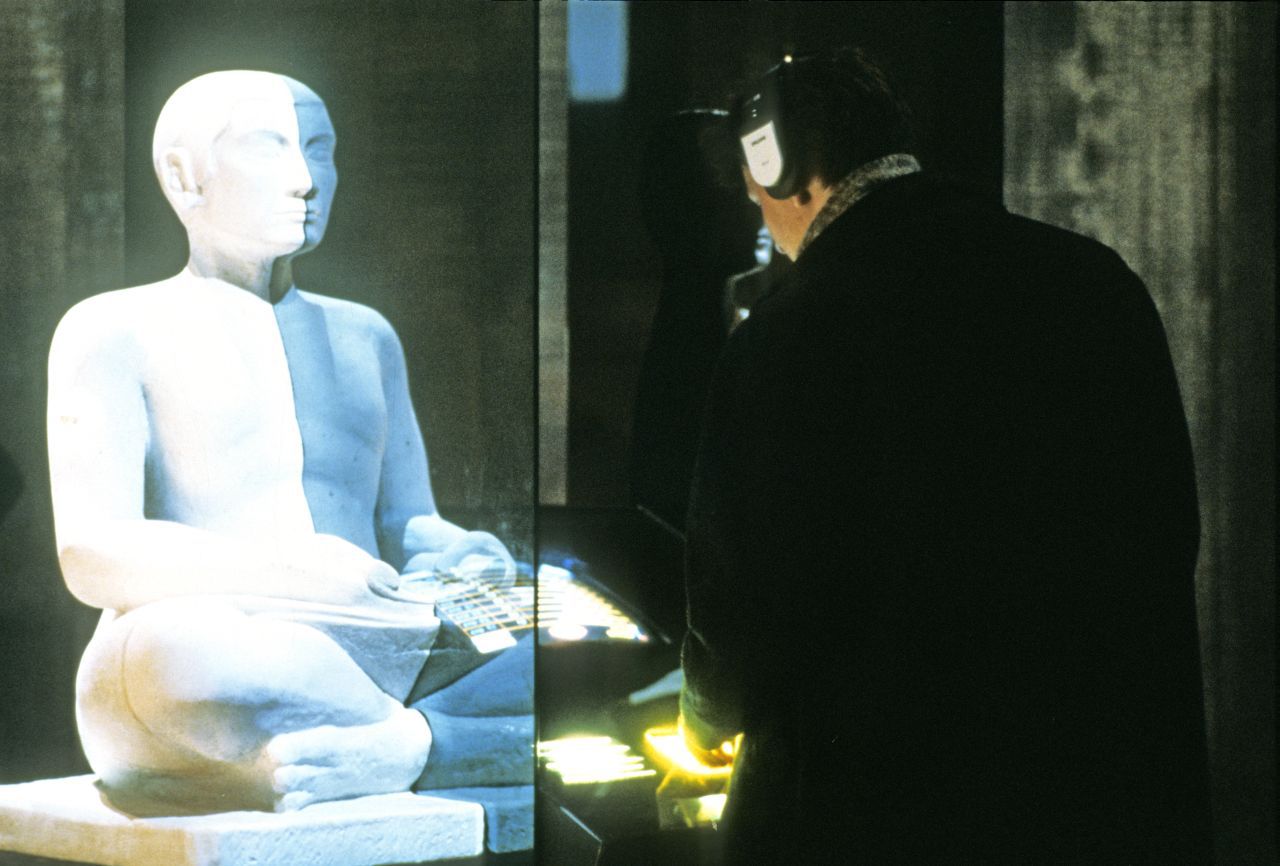

In my talk at the Nexa Institute, I use both shows as a way to highlight the problems of preserving the artworks displayed and the impossibility of re-staging each show in the present day.

Les Immatériaux (exhibition) Centre Pompidou, Paris (1985) via Les Immatériaux: A Conversation with Jean-François Lyotard and Bernard Blistène by Tara McDowell. All images courtesy of Centre Pompidou - MnamCci - Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris

Les Immatériaux (exhibition) Centre Pompidou, Paris (1985) via Les Immatériaux: A Conversation with Jean-François Lyotard and Bernard Blistène by Tara McDowell. All images courtesy of Centre Pompidou - MnamCci - Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris

I reach this conclusion in spite of Antony Hudek’s suggestion that “Les Immatériaux could be considered a self-remembering exhibition.” because of “its self-reflexivity and auto-archiving impulse,”Antony Hudek “From Over- to Sub-Exposure” (2011)

Empirically speaking, Hudek has a point. The exhibition generated an abundance of documentation:

- Although there was no traditional exhibition catalog, the exhibitors printed a collection of unbound cards for each site (61 total) and a bound retrospective that constituted a “making of.”

- A collection of electronic messages with 26 participants discussing 50 terms set by the curator was also published as a volume titled Epreuves d’écriture.

- Sociologist Nathalie Heinich published an analysis using data collected on the visitors’ movements through, and reactions to, the exhibition.Christian Carrier (ed.): Les Immatériaux au Centre Georges Pompidou en 1985. Etude de l’evenement exposition et de son public. Paris: EXPO-MEDIA, 1986 (incl. texts by Yannick Courtel, Nathalie Heinich, Jean-François Lyotard, Charles Perraton)

- The piece Les Variables Cachées in zone 12 (the “matrice” strand) surveyed visitors in a computer terminal and projected results.

- And finally, a suggested but never realized “mise-en-carte” would have allowed the visitor to swipe a magnetic card at each site in the exhibition, culminating in a printout that summarized their trip through the non-linear experience, location by location.

But even with all of this, John Rajchman, who attended the show, had this to say when recalling the show in 2009:John Rajchman “Les Immatériaux or How to Construct the History of Exhibitions: Landmark Exhibitions Issue” Tate (2009)

Documentation of this exhibition is now hard to come by; and even though I have held onto the catalogues and related materials from the press-kit for the review I wrote at the time, it still seems difficult to bring into focus what I saw then.

Digital artifacts that are the result of complex processes are extremely fragile. This is true of cultural objects produced in 1968, in 1985, and in 2020. They quickly slip into oblivion. If we value our own culture, we must find ways to preserve these artifacts and their digital/physical execution environments.

The Talk

Download the Software Preservation in Networked Art slides.

Download the Software Preservation in Networked Art slides.

A brief survey of net.art from the 1990s and early 00s demonstrates the challenges faced by curators and preservationists. The absence of physical art objects presents the central problem. Although some works of art can be meaningfully reproduced, often all that is left is documentation and some physical artifacts.

This situation presents countless trappings because art’s borders are necessarily blurry: works of engineering must provide their prescribed functionality; results from scientific processes must be reproducible; but art’s subtle intent is always in danger of being overshadowed.

The savvy archivist knows that every artist casts human concerns using the tools of their day. Net.art is shaped by both the computer and the medium of telecommunications. A common mistake made by preservationists and curators is to convey this artwork as a relationship between things, when the the pieces are really about relationships between people.

While individual digital artifacts are trivial to reproduce if stored properly, the interdependent digital systems that lay the foundation for networked art pieces are often impossible to recreate. This seminar addresses the existential questions, current best practices, and future technologies that may help combat a generational loss of culture.

The Recording

Unfortunately, the recording of the talk was cut a little short. This is what was captured from our session.

Recommended Readings

The Nexa Institute asked me to submit a list of recommended readings related to my talk. I’m happy to share them once again here:

- Berry, David M. “The Post-Archival Constellation: The Archive under the Technical Conditions of Computational Media”. Memory In Motion, 2017, 103-126. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1jd94f0.8.

- Connor, Michael J, Aria Dean, and Dragan Espenshied. The Art Happens Here: Net Art Anthology, 2019.

- Kraynak, Janet. Contemporary Art and the Digitization of Everyday Life. University of California Press, 2020.

- Collections

- Grau, Oliver, Janina Hoth, and Eveline Wandl-Vogt. Digital Art Through the Looking Glass: New Strategies For Archiving, Collecting and Preserving in Digital Humanities. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2019.

- Baas, Jacquelynn. Buddha Mind In Contemporary Art. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004.