The Storm

The US Capitol Building on 6/January/2021. LEAH MILLIS/Reuters

The US Capitol Building on 6/January/2021. LEAH MILLIS/Reuters

In the arms race for people’s attention, technology companies have invested countless billions into capturing our eyes and ears. Their algorithms that determine how and when information is displayed shapes our reality.

But information is delicate. The veracity of any individual statement can shift depending on its context or even how many times it is repeated. Small changes can have subtle but insidious effects.

Changes to the context and dissemination of information do not announce themselves like a violent tempest. But ideas can mark the beginnings and ends of nations. Perhaps Andrew Ross Sorkin captures the subtle absurdity best:

So Trump has access to the nuclear codes but he can't Tweet or post to Facebook.

— Andrew Ross Sorkin (@andrewrsorkin) January 7, 2021

Advertising companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Google are powerful enough to shift reality. The algorithms that do the work of displaying information are completely secret. No outside person can study them; no outside technology can interoperate with them. The only way to make meaningful changes within these systems is to know them. Without change, the storm will continue to build.

The Truth

Yesterday’s insurrection grabbed headlines worldwide, but the people were already in the building before the mob arrived. Members of Congress and the President of the United States explicitly sympathize with the insurrectionists.The President mostly peddles malinformation to his supporters while many in Congress support his efforts by spreading misinformation. The differences are subtle but important. I outline them in Disinformation Strategies and Tactics.

The shared convictions run so deep that some lawmakers continued to recklessly promote misinformation after an unprecedented day of violence.

Here is a small selection of highlights from the New York Times’ fact-checking of the Congressional Debate on Ratifying the Election Results. This debate happened after the day’s chaos.

It’s been proven that these [voting] machines are connected and that they can be hacked.

How can this election be certified using a system that still displays after two months that 205,000 more votes were cast in Pennsylvania than people who voted?

The Washington Times has just reported some pretty compelling evidence from a facial recognition company showing that some of the people who breached the capitol today were not Trump supporters. They were masquerading as Trump supporters, and in fact were members of the violent terrorist group antifa.”

It’s not uncommon for lawmakers to object to counting a state’s electors. Some Democrats in the House of Representatives did the same in 2001 and 2017 after the president-elect lost the popular vote. What struck me about last night was the commitment to dubious information even after the day’s events.

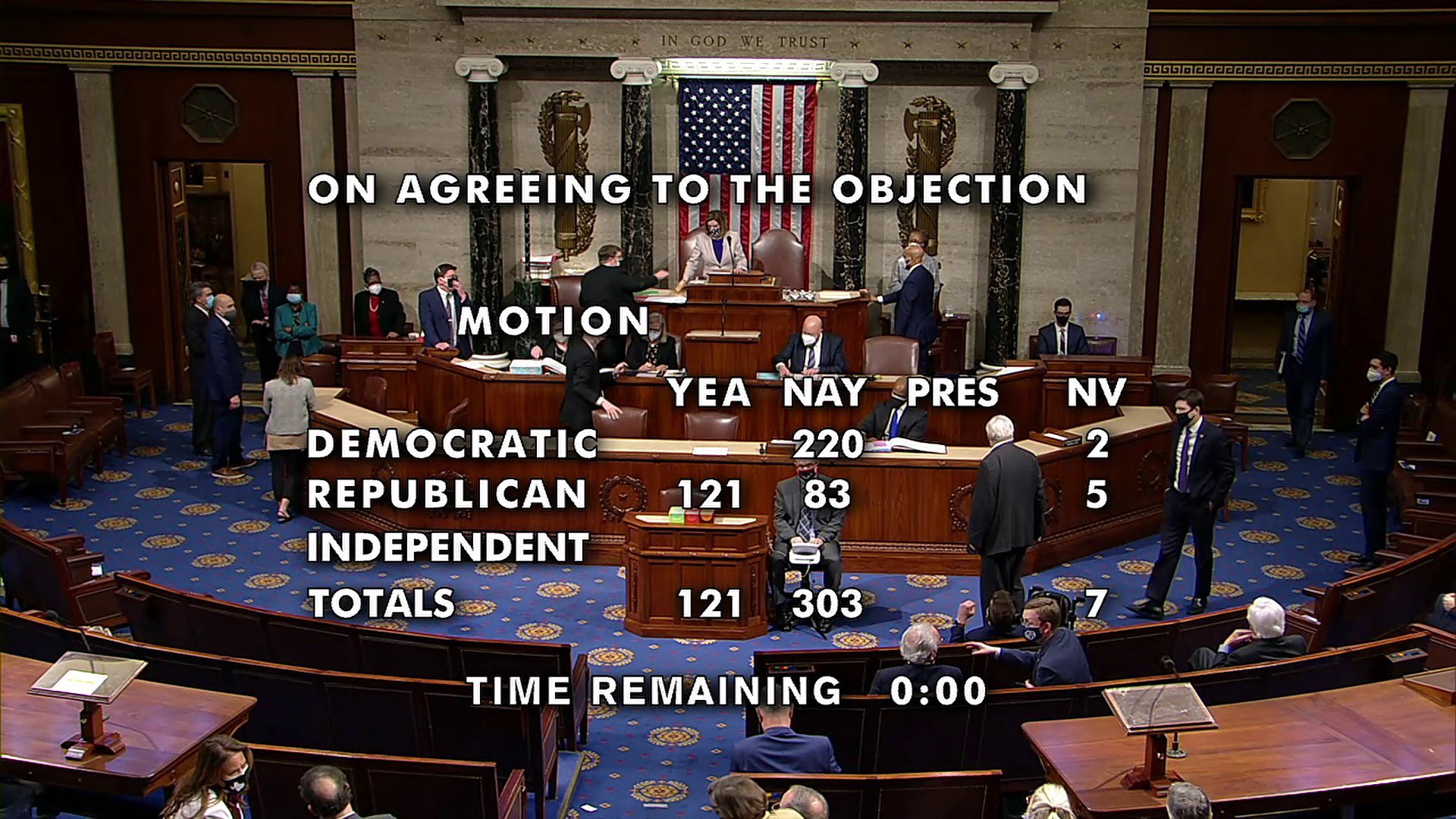

A vote was taken on an objection to the legitimacy of votes cast in Arizona. 121 Republicans in the House of Representatives officially stated that the election in Arizona was illegitimate. Only 83 Republicans disagreed.

The final vote on the objection to Arizona’s electoral votes.

The final vote on the objection to Arizona’s electoral votes.

Even before the insurrectionists entered the Capitol Building, their advocates were already inside.

Narrowcasting

If we live in an “information society” and we get our information from the “information superhighway,” then misinformation, malinformation, and disinformation are just different parts of the landscape we must accept.

When we invent a technology, we also invent its related disaster, as Paul Virilio so eloquently illustrated. You can’t have a car crash without first inventing a car.

The people who stormed the Capitol were armed with Truth. They entered with ease because the Truth was already inside the building. This is the disaster of the internet. More specifically, it is the disaster of a type of communication that the internet enables called “narrowcasting.”

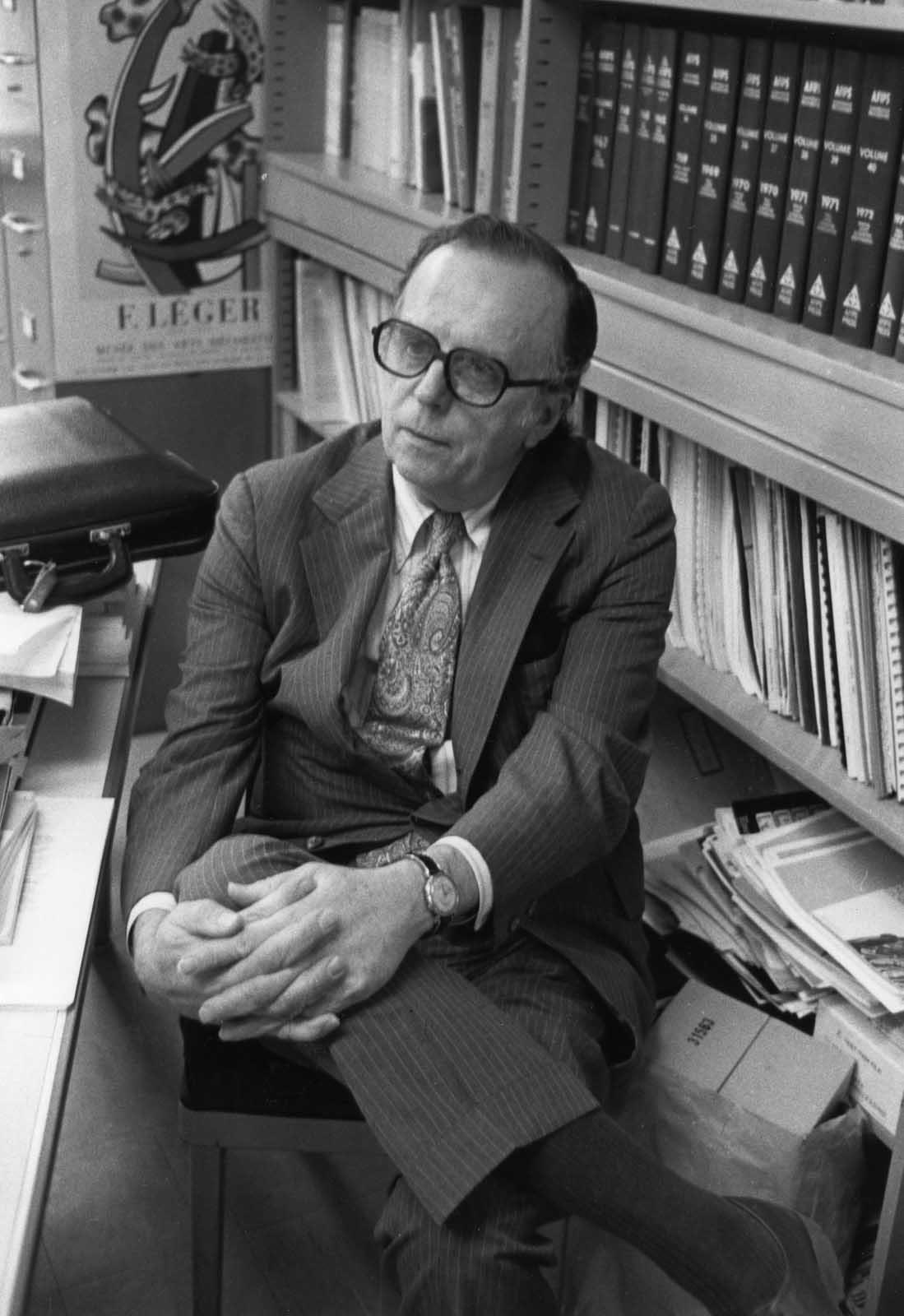

The term “narrowcasting” was coined by none other than J.C.R. Licklider in 1967. As previously mentioned on Beyond the Frame, Licklider is a considered a visionary founder of the internet. J.C.R. Licklider (above). From “On the Internet, We Are Either Artists or Bureaucrats” - “At his best, Licklider was an imaginative manager who empowered creative individuals across computing. […] At his worst, Licklider was a technocrat. He effectively navigated the military bureaucracies of the Cold War by promising predictive models using complex data to bolster counterinsurgency efforts at home and around the world.”

J.C.R. Licklider (above). From “On the Internet, We Are Either Artists or Bureaucrats” - “At his best, Licklider was an imaginative manager who empowered creative individuals across computing. […] At his worst, Licklider was a technocrat. He effectively navigated the military bureaucracies of the Cold War by promising predictive models using complex data to bolster counterinsurgency efforts at home and around the world.”

But when he coined narrowcasting, he was ruminating on the educational possibilities of satellite television.J.C.R. Licklider, “Televistas: Looking Ahead Through Side Windows”, Public Television: A Program For Action, (New York: Carnegie Commission on Educational Television, January 26, 1967) (pp. 212).

I should like to coin the term ‘narrowcasting,’ using it to emphasize the rejection or dissolution of the constraints imposed by commitment to a monolithic mass-appeal, broadcast approach.

His utopic vision outlined a variety of television networks that served the needs of specialized audiences. It is a fine vision with many benefits. But the problem is that Licklider was a technocrat and a salesman. He couldn’t talk about the car crash - he couldn’t even talk about the seat belt - because everything was in service of raising the money to build a car.

Almost all of his writings on a technology-enabled future promise great things for humankind. They rarely mention possible drawbacks, let alone the impact of information technology on something as fragile as a democracy.

In the heyday of 1990s/2000s dotcom fever, I remember some of us raising concerns about society’s change from broadcasting information to narrowcasting information.It’s a pretty quiet group. I’m having trouble citing papers or even forum/usenet posts from the 1990s/early 2000s. If any reader can point me in the right direction, please contact me.

We asked, “What is the impact of an internet that only connects people with the information they want to know?” Twenty years later, I believe we have our answer.