Traditional contact tracing can help contain a contagion. But it is a laborious, imprecise process that relies on human memory. Apple and Google co-developed iOS and Android software to automate the process while maintaining user privacy. This post explores two questions:

- How does it work?

- How effective can it be?

How It Works

Luca Ferretti et al., “Quantifying SARS-Cov-2 Transmission Suggests Epidemic Control With Digital Contact Tracing”, Science, 2020, doi:10.1126/science.abb6936.

Luca Ferretti et al., “Quantifying SARS-Cov-2 Transmission Suggests Epidemic Control With Digital Contact Tracing”, Science, 2020, doi:10.1126/science.abb6936.

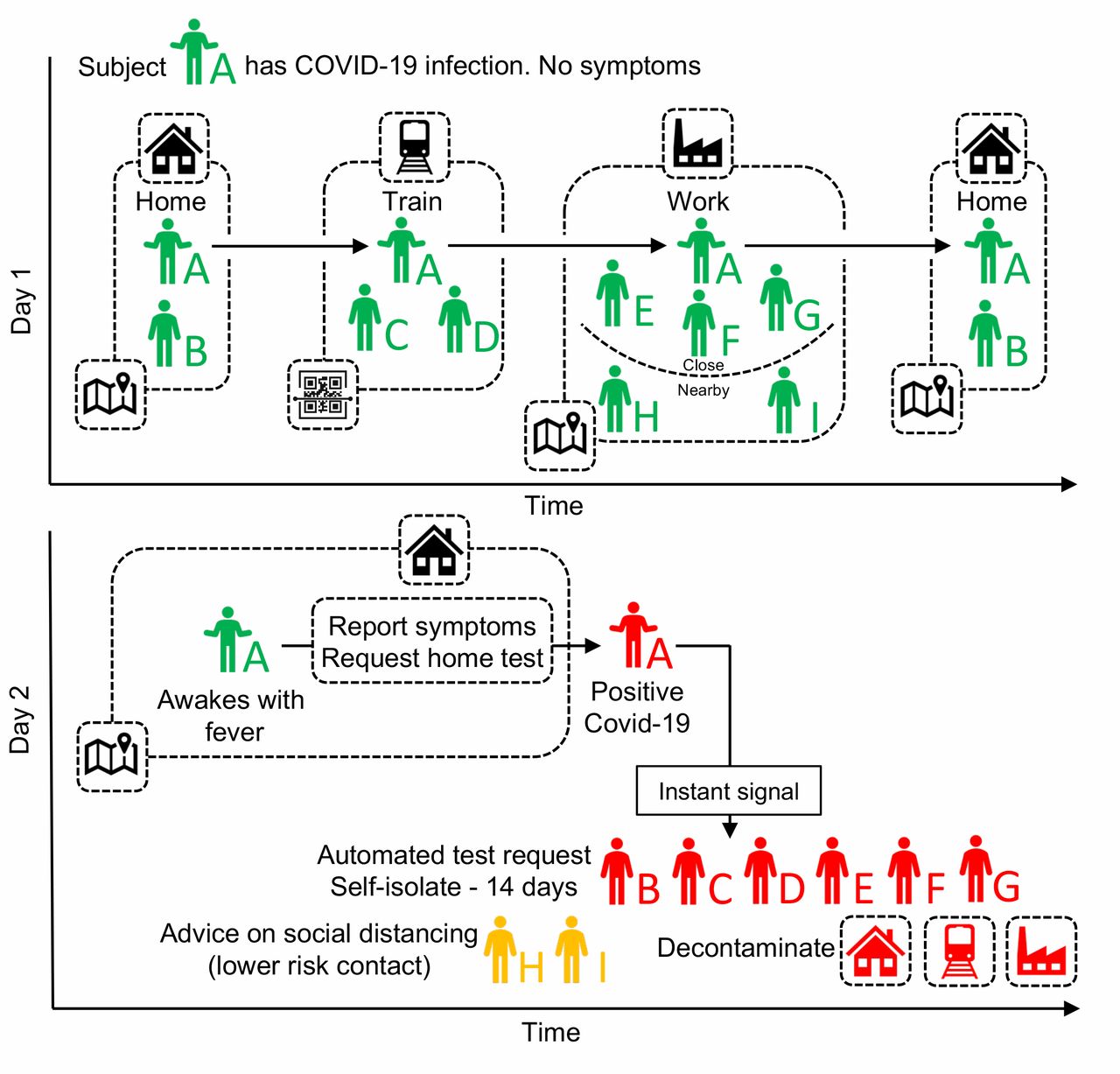

Automated exposure notification lets Person A’s mobile device alert Person B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I if they are diagnosed with COVID-19. Several nations already have some form of contact tracing in place. But keeping a log of every citizen’s contacts immediately raises legitimate privacy concerns.![]() Apple/Google nearly abide by the Nexa Institute’s “Tracciamento dei contatti e democrazia: lettra aperta ai decisori” (Contact tracing and democracy: open letter to decision makers) and CCC’s “10 requirements for the evaluation of ‘Contact Tracing’ apps.” Nexa Institute states that digital contact tracing must be 1 - voluntary, 2 - a single app with a single purpose that is used for a limited time, 3 - the software must be publicly available, with complete source code, and free software licenses, and 4 - adopt decentralized technologies. Apple/Google nailed 1 & 4, leave 2 open for governments to decide and unsurprisingly fall short on point number 3.

Apple/Google nearly abide by the Nexa Institute’s “Tracciamento dei contatti e democrazia: lettra aperta ai decisori” (Contact tracing and democracy: open letter to decision makers) and CCC’s “10 requirements for the evaluation of ‘Contact Tracing’ apps.” Nexa Institute states that digital contact tracing must be 1 - voluntary, 2 - a single app with a single purpose that is used for a limited time, 3 - the software must be publicly available, with complete source code, and free software licenses, and 4 - adopt decentralized technologies. Apple/Google nailed 1 & 4, leave 2 open for governments to decide and unsurprisingly fall short on point number 3.

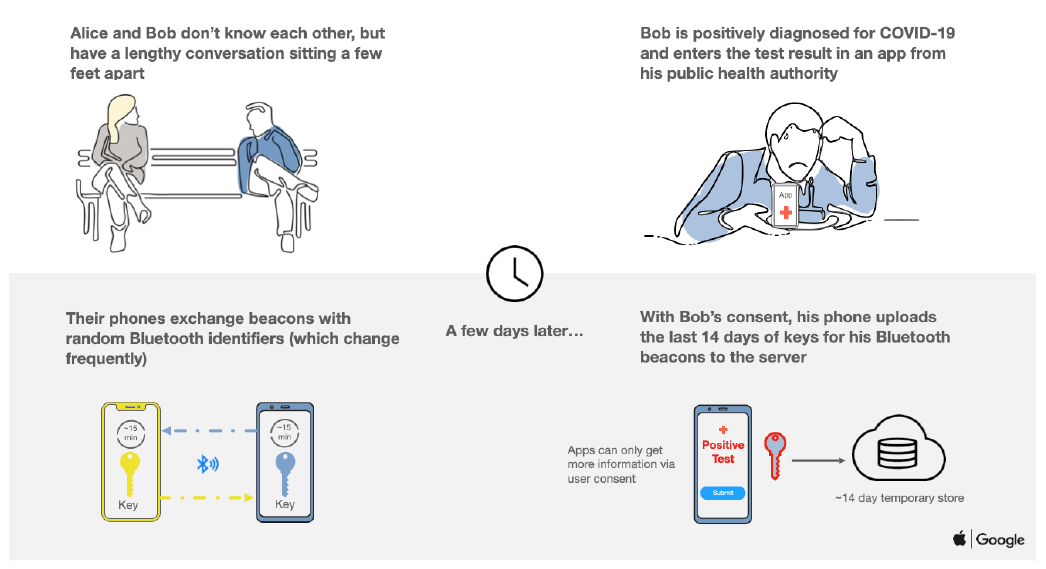

Apple and Google decided to bake an automated exposure notification service into their portable devices. The software will enable intra-device information exchange over Bluetooth while keeping each individual’s identity a secret.

Balancing Identity and Privacy

Apple Inc., Exposure Notification Frequently Asked Questions May 2020 v1.1

Apple Inc., Exposure Notification Frequently Asked Questions May 2020 v1.1

Identity is understood by using a set of keys.

- Every device creates a unique and permanent master tracing key.The key is a single 256-bit sequence. High entropy is used to prevent duplicates. Each device generates their own master tracing key and will never know the master tracing key of any other device.

- Every day a new daily tracing key is derived from the master tracing key.A daily tracing key is 128-bit, half the size. It is deterministically derived by hashing the master tracing key with the Unix epoch day number (the number of days since January 1st, 1970). The master key cannot be reverse-engineered from the daily tracing key - a mathematically proven guarantee.

- Daily tracing keys are shared with other devices when they come close to one another (bottom left in the above illustration).

- Daily tracing keys are only uploaded to a central database if a user tests positive (bottom right in the above illustration). In this case, they are deemed diagnosis keys.

- Every device regularly asks the central server for new diagnosis keys. The device alerts the user if a set of diagnosis keys match some set of daily tracing keys held on the device. Remember, a device only captures daily tracing keys when it comes into close contact with another person’s device (top left in the above illustration).

At no point is the key tied to the identity of its holder. To be sure, I’ll quickly audit the three root sources of concrete identity in the system:

- The master tracing key, which is never given to anyone, ever.

- The address of each Bluetooth device. After all, devices must know each other’s address to find one another.

- The cell phone’s Internet Protocol Address (IP Address).

Your Bluetooth address is called the MAC address. Exposure notification apps will send Rolling Proximity Identifiers from this address to any device that wants to listen. They are secure because both of these signatures change randomly every 10-20 minutes, so it’s impossible to link the Rolling Proximity Identifier with any specific hardware.Bluetooth metadata is also encrypted.

As for identifier number 3, cell phone IPs change quickly and cannot be used to geolocate an individual device.

The data is ephemeral, like the contagion itself. Right now it is aged out every 21 days.

The data is local, like the contagion itself - it spreads with person-to-person contact. The local repository of the data only shares diagnosis keys with those who were in contact. Large national and international repositories are not useful.

Dangers

The system Apple and Google have created seems cryptographically sound, but there are still dangers.

- Apple and Google are just providing an API, the apps are built by someone else. If an app also chooses to store your GPS information, for example, it will make these precautions moot.

- False positives due to technological limitations: you can be “close to someone” that is on the other side of a wall.The software can record information about the strength of a Bluetooth signal. Thresholds of time and distance can be set to reduce false positives. Ideally, these settings would be determined by epidemiologists.

- False negatives due to technological limitations: COVID-19 can be transmitted by surface contact.

- Spoofs of false positives: trolls could claim a diagnosis even when perfectly healthy. The proverbial pulling the fire alarm when there is no fire.

- The software is not open source. We just have to trust Apple and Google.The Apple/Google solution is similar to the open source effort, DP-3T. Unfortunately, they decided on a closed-source re-implementation.

For further technical information, Security Now! episodes #762 and #764 go into even greater detail.

Are They Effective?

TL;DR: no one knows.

In the Apple/Google model, the device owner must opt in. Exposure notifications will be off by default. But some epidemic models indicate a need for incredibly wide adoption.

The team estimates that 56% of the general population must use the app to halt the outbreak. Prof Fraser said that equated to 80% of all existing smartphone owners, based on data from Ofcom.Fraser is a co-author on the aforementioned “Quantifying SARS-Cov-2 Transmission Suggests Epidemic Control With Digital Contact Tracing”, Science, 2020, doi:10.1126/science.abb6936.

Nature paints a gloomy picture of adoption in Singapore, where the TraceTogether app is already deployed.

Much attention has also been paid to Singapore’s TraceTogether app, which now has more than one million users. Although this amounts to roughly one-fifth of Singapore’s population, it still means that in any encounter between two randomly chosen people, there is only a 4% chance that both will have the app.“Show Evidence That Apps For COVID-19 Contact-Tracing Are Secure And Effective”, Nature 580, no. 7805 (2020): 563-563, doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01264-1.

Health policy experts like Mark McClellan call for “aggressive case identification and contact tracing.” He and his colleagues note that “existing local public health capacity for such response activities is very limited” in the United States. However, they are not very optimistic about the usefulness of automated exposure notifications:

Cell phone-based apps recording proximity events between individuals are unlikely to have adequate discriminating ability or adoption to achieve public health utility, while introducing serious privacy, security, and logistical concerns. Instead, timely contact tracing can be achieved through strengthened public health case investigation augmented by technology and community-level collaborations.Mark McClellan et al., “A National COVID-19 Surveillance System: Achieving Containment”, Page 9, April 7, 2020.

Digital security expert Bruce Schneier thinks the idea is “just plain dumb.”

Assume you take the app out grocery shopping with you and it subsequently alerts you of a contact. What should you do? It’s not accurate enough for you to quarantine yourself for two weeks. And without ubiquitous, cheap, fast, and accurate testing, you can’t confirm the app’s diagnosis. So the alert is useless.

Schneier is certainly right on one point: exposure notifications must be coupled with easy, ubiquitous testing. He also worries that many people will contract the virus without ever being alerted, eroding the public’s trust and confidence in the technology.

EDIT 12/May/2020: The MIT Technology Review has reported that “Nearly 40% of Icelanders are using a covid app—and it hasn’t helped much”. The article quotes Gestur Pálmason of the Icelandic Police Service, “I would say it has proven useful in a few cases, but it wasn’t a game changer for us. [… Its impact] has been exaggerated by people eager to find technological solutions to the pandemic.”The app also looks like it raises a myriad of privacy concerns. From the same article: Rakning C-19, which launched in early April, was hailed as a way to “make the tracing of transmissions easier” at the time. It tracks users’ GPS data to compile a record of where they have been, allowing investigators—with permission—to look at whether those with a positive diagnosis are potentially spreading the disease.

The Apple/Google technology will be the most widely available technology intended to curb disease transmission while maintaining citizen privacy.An important subplot to this technology is Apple/Google’s marketplace power to force its adoption. Germany was exploring other options, until recently. Chancellery Minister Helge Braun and Health Minister Jens Spahn said in a joint statement that Berlin would adopt a “decentralised” approach to digital contact tracing, thus abandoning a home-grown alternative that would have given health authorities central control over tracing data. […] Germany as recently as Friday backed a centralised standard called Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (PEPP-PT), which would have needed Apple in particular to change the settings on its iPhones. When Apple refused to budge there was no alternative but to change course, said a senior government source.

Any possibility of effectiveness will likely depend on a variety of non-technical factors.

In contrast, Dunja Mijatovic, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, has highlighted several other technology-based policies rolled out under the auspices of curbing the spread of COVID-19. They aren’t pretty.

- Russia: “the government has resorted to facial recognition cameras to enforce quarantine orders without guarantees that such technology will not be used for other purposes.”

- Azerbaijan: “citizens must report their movements by ISM’S to an electronic system, potentially enabling the police to monitor them.”

- Montenegro: “the government published on its website the names and the addresses of people who have been ordered to self-isolate upon their return from abroad.”

- Poland: “a mandatory government-provided app requires quarantined people to take time-stamped selfies with GPS coordinates several times a day. Failure to comply with the task may result in police intervention and lead to a hefty fine.”

- Turkey: “also announced a similar mandatory app to follow the whereabouts of persons who have been tested positive for COVID-19.”

- United Kingdom: “the Guardian newspaper revealed that technology firms processed the confidential personal data of patients without transparency or accountability.”

Information is a critical tool to curb the growth of any pandemic. It matters how it’s collected.