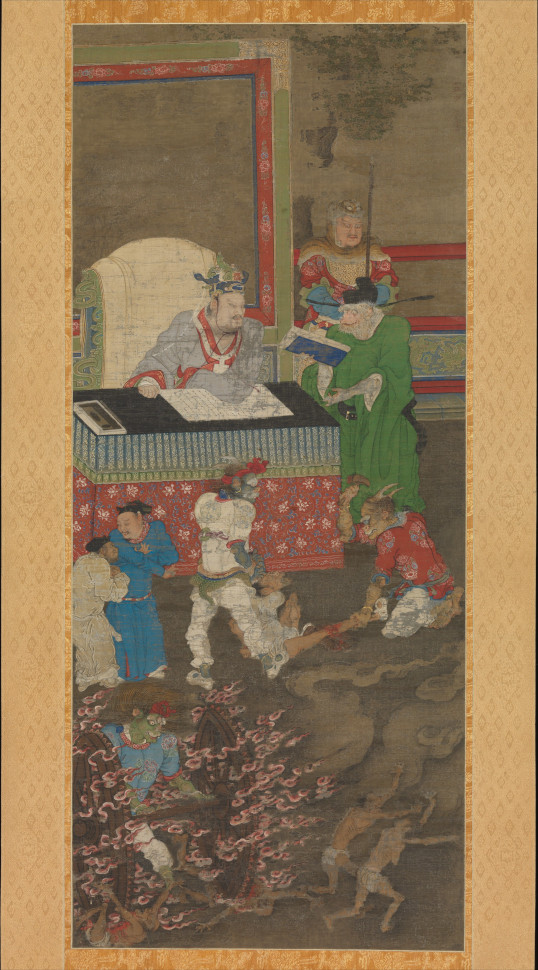

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ten Kings Of Hell, image, 1195. “[The series] transforms the Indian Buddhist view of judgment after death into a typically Chinese bureaucratic process.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ten Kings Of Hell, image, 1195. “[The series] transforms the Indian Buddhist view of judgment after death into a typically Chinese bureaucratic process.”

In art-making one sees oneself as a river but also as the boat on the river, periodically tossed on to the shore only to be caught up in the river’s momentum once again. When this vision is achieved, creative individuals are able to move with excitement from one project to the next, from one idea to the next, completing one and beginning another, in an endless tide of creation, cessation, and creation again. If you are lucky, you can surround yourself with others tossed about by the same, tumultuous waters. And if you are very lucky, while on your own journey, they will invite you to enter into and comment on theirs.

On Sharing

The other night I was talking to a friend about sharing political opinions on Twitter. As I watch from Italy, the United States is suffering a crisis of conscience as it attempts to navigate a pandemic. Looming in the background is a presidential election in November where disinformation is being spread about the basic mechanisms of democracy - most recently regarding the legitimacy of mail-in ballots - from the very head of the government itself.

I still believe that the best internet is the internet that engenders community and conversation. A network of thought is like a community of artists. Each person who shares their small creative act invites a response. An observed reaction cannot be unseen. The river only flows one way.

The bureaucrat is a slave to the machine. They move information along uncritically. No conversation is desired or necessary; the acts are justified by the process itself.

The performative aspects of social media - likes, retweets, and chasing engagement - are different than the conversational tools of message boards and newsgroups. “Engagement,” as it is called in the analytics dashboard, is cosmetic. It obscures the difference between conflict and conversation.

So my line is simple - I share political opinions online when I feel like I have something to contribute to a conversation. And that’s not very often.

Conversation and Community

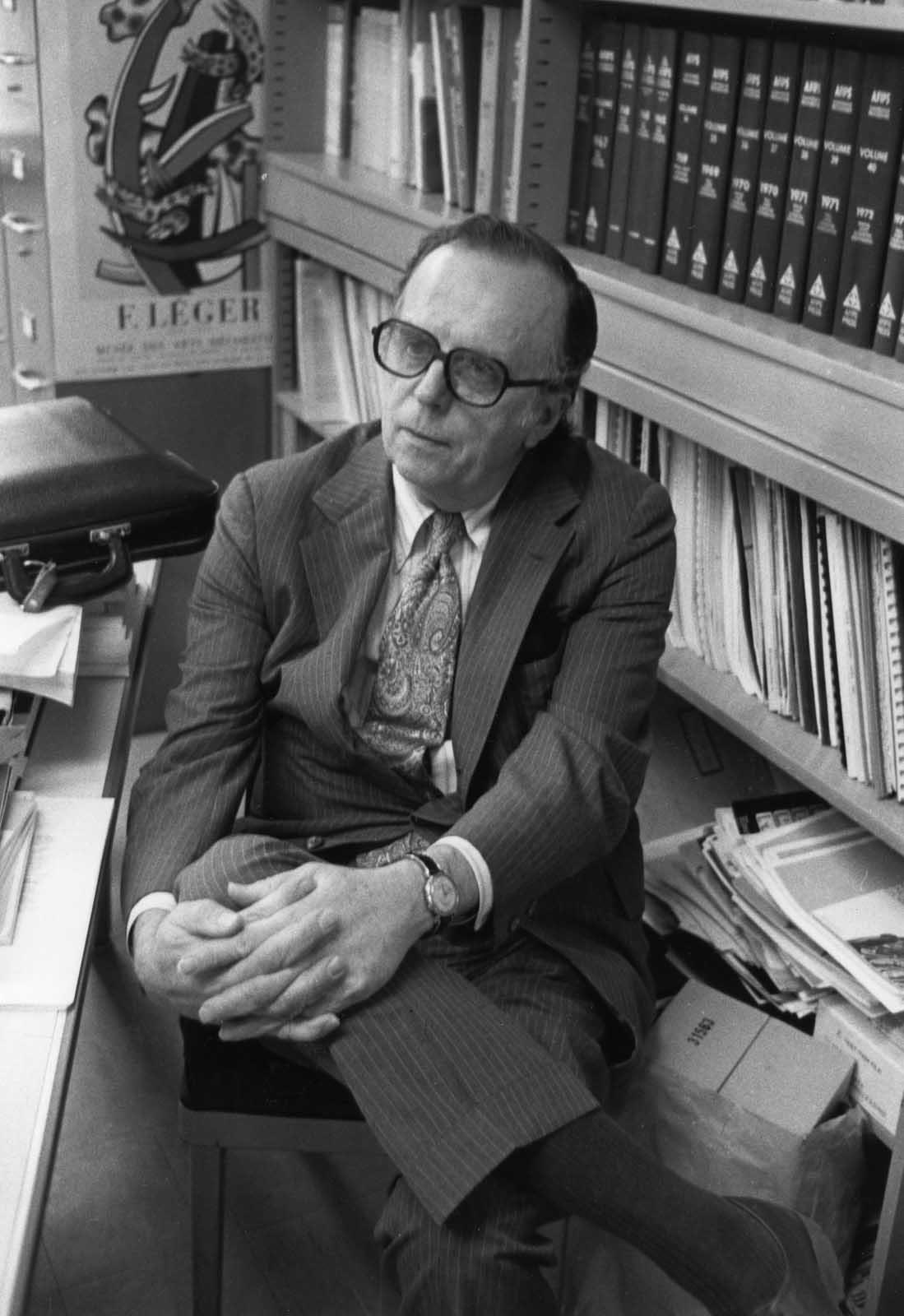

J.C.R. Licklider (1915-1990). Photographer Ben Shneiderman remembers, “I enjoyed his visit to our group at the University of Maryland in April 1979, when I took this photo, and soon after appreciated his kindness as my host to speak at MIT.” (Ben Shneiderman, J.C.R. Licklider, image, 1979.)

J.C.R. Licklider (1915-1990). Photographer Ben Shneiderman remembers, “I enjoyed his visit to our group at the University of Maryland in April 1979, when I took this photo, and soon after appreciated his kindness as my host to speak at MIT.” (Ben Shneiderman, J.C.R. Licklider, image, 1979.)

Why isn’t the internet better at engendering conversations? The precedent was set early on. Consider what networking pioneer J.C.R Licklider published in 1968 on online communities:J.C.R. Licklider and Robert W. Taylor, “The Computer As A Communication Device”, Science And Technology, April 1968.

In most fields they will consist of geographically separated members, sometimes grouped in small clusters and sometimes working individually. They will be communities not of common location, but of common interest.

Licklider argued that people would be happier and more productive if they participated in communities of shared interest rather than “accidents of proximity.”Licklider’s vision for a “network of networks” was profound its scope and relatively unique in its time. Beyond communities of interest, he shares three other outcomes of a networked society: “Second, communication will be more effective and productive, and therefore more enjoyable. Third, much communication and interaction will be with programs and programmed models […]. And, fourth, there will be plenty of opportunity for everyone to find his calling, for the whole world of information, with all its fields and disciplines, will be open to him.” (J.C.R. Licklider and Robert W. Taylor, “The Computer As A Communication Device”, Science And Technology, April 1968.)

At least in my case, his vision has come to pass. I communicate with programmers, artists, and researchers around the world from my home in Turin, Italy.

The Artist is the Bureaucrat

At his best, Licklider was an imaginative manager who empowered creative individuals across computing. His work had a tremendous impact on the internet, graphical user interfaces, and computer science education.In the video below, Licklider warns that the internet will place us on “a new technological base for intellectual efforts before our ponderous social processes will let us. I think more people outta get in there and think about the social process.” Another well-formulated forecast.

At his worst, Licklider was a technocrat. He effectively navigated the military bureaucracies of the Cold War by promising predictive models using complex data to bolster counterinsurgency efforts at home and around the world.See Yasha Levine on Licklider and Ithiel de Sola Pool’s 1969 ARPA Cambridge Project: “Once complete, it would allow any intelligence analyst or military planner connected to the ARPANET to upload dossiers, financial transactions, opinion surveys, welfare rolls, criminal record histories, and any other kind of data and to analyze them in all sorts of sophisticated ways: sifting through reams of information to generate predictive models, mapping out social relationships, and running simulations that could predict human behavior.” (Yasha Levine, Surveillance Valley: The Rise Of The Military-Digital Complex (PublicAffairs, 2018))

This tension is most apparent in Licklider’s writing on community. Building a healthy community that engenders fruitful conversation is a difficult endeavor. It requires a certain skill and a lot of hard work. Most people who manage book clubs or internet forums do their work unpaid. Their effort is yet another form of labor that no technocratic system can seem to properly compensate or value. The very linchpin of community building goes unmentioned in Licklider’s musings on online communities - as if the technology itself was the solution. Sadly, Silicon Valley has done little to correct Licklider’s oversight sixty years later.

Update March, 19, 2024: Joe Hallenbeck of Joe’s Digital Garden made a couple notes about this post and “Truth Storms the Capitol” in “Small Web” and “Disinformation Theory.”

First off, Hallenbeck highlights an important tendency to shade both narrowcasting and broadcasting in a negative light:

Narrowcasting is the tailoring of a presentation to a specialized audience. This is opposed to broadcasting with is crafted for mass appeal. An narrowcast internet is one that contains only the information that the audience wants to know and none of the information that would challenge or be disagreeable to them. On a side note, it is interesting that broadcasting itself has somewhat of a negative connotation as it has historically been framed as a means of shaping group-think on the nation-state level.

As Rich McCulloch and Ben Litherland explore in the most recent episode of Ill Effects, “Can YouTube turn you into a Flat Earther?,” narrowcasting algorithms have been blamed for convincing people the earth is flat and 9/11 was an inside job. While at the same time, broadcast media has been cited as the culprit of political violence and decaying morality.

It’s as if all media holds incredible power! But the solutions I’ve seen across the United States and Europe rarely promote the idea of media literacy. Nations run by bureaucrats don’t aspire to create a citizenry of engaged, interrogative artists.

At the risk of making bureaucrats a kind of archetypal boogeyman, I also quite like this observation made by Hallenbeck:

A bureaucrat, however, is a slave to the machine. They opine because it is required – favorite, retweet, boost and register their engagement in the most formal and banal of processes. Shouting into the void is not the basis for a community.

Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and their products are the logical culmination of Licklider’s vision. One preeminent Silicon Valley company, Stripe, has even bought the publication rights of The Dream Machine and placed their hero on the cover. Cover of The Dream Machine published by Stripe Press.

Cover of The Dream Machine published by Stripe Press.

I have read The Dream Machine and take no particular exception to its contents. But this juxtaposition between Silicon Valley and Licklider is the perfect distillation of “On the Internet, We Are Either Artists or Bureaucrats.”