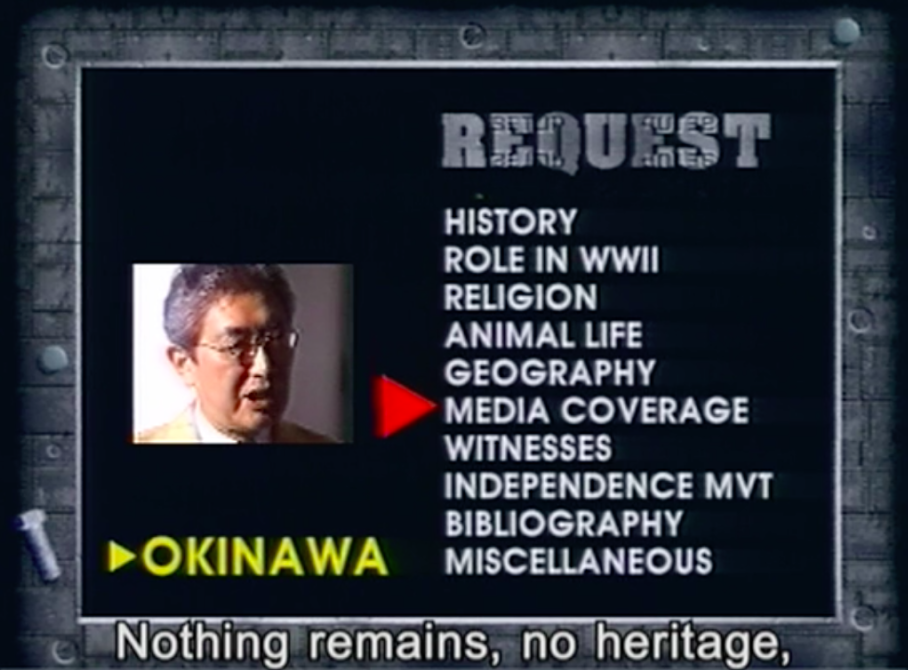

The OWL database from Level Five. (Chris Marker, Level Five, film (France: Les Films de l’Astrophore, Argos Films, 1997).)

The OWL database from Level Five. (Chris Marker, Level Five, film (France: Les Films de l’Astrophore, Argos Films, 1997).)

Chris Marker’s Level FiveLevel Five is available to watch on Mubi.

(1997) moves through a computer network as a space of memory. The film is something of a travelogue, like Joseph Brodsky’s writings on Venice or Chris Markers’ own Sans Soleil, but it traverses records of events through virtual space. The main character explores a hierarchical database called OWL as she finishes making the fifth level of an incomplete game she inherited. The events in the game are based on the Battle of Okinawa during World War II; the film follows her exploration of this battle and the pathways of the game’s deceased originator.

The virtual journey draws a distinction between information and memory. In his essay, Forms of Memory: Close-Up on Chris Marker’s “Level Five”, Benjamin Crais defines memory as “an orderly collection, a certain arrangement of signs, traces, and monuments” and information as “a matter of indifferently equivalent facts.” He suggests that Level Five defines a closer relationship between the two, where “personal-historical-cultural memory” is completely expressed through a database - a cornerstone of information technology.Benjamin Crais, “Forms Of Memory: Close-Up On Chris Marker’S "Level Five"”, MUBI, 2017. Crais’ work references Jacques Ranciere, “Documentary Fiction: Marker and the Fiction of Memory”, Film Fables (157).

Increasingly, we are living in a world where cultural and personal memory are not stored in minds and transmitted through bodies, but stored in databases and transmitted through machines. Storing memory and modeling time is a hard problem, but one that demands attention.

In part 1 of Storing Time, I looked at some of the current issues related to manipulating and modeling time. I used the popular Java Time library and demonstrated the basics in Clojure.

Part 2 will look at one approach for storing and manipulating time in plain text. It is a simple system for personal recording keeping. In this case, it is a record of my professional activities that can be used to generate websites, resumes, and my curriculum vitae.

I’ll conclude by taking a cursory look at the problems of archiving time in Unix systems. If you’re not interested in the specifics of storing and reading Java Time in Clojure/edn, please skip ahead to the last section.

Time Literals

As stated in Part 1, I want a time format that is:

- Easy to write and read: add and update events in a plain text file

- Easy to format: automatically change a date’s display depending on context, calculate and display a span of time, etc…

Part 1 demonstrated how Java Time can be used to format dates. I’ll expand on that later in Part 2. But first, I need to explain how working with time literals (rather than Java Time objects) will make time easy to read and write from a plain text file.

Literals

Literals return themselves when evaluated.Literals and expressions in this section can be evaluated as a runnable notebook in Nextjournal. The notebook also includes more detailed information about Java Time and Joda Time in Clojure.

- When

3is evaluated in Clojure, the system returns3. - When

"I have a dream"is evaluated in Clojure, the system returns"I have a dream". - When

(+ 3 7)is evaluated in Clojure, the system returns10.(+ 3 7)is not a literal.

Clojure literals include numbers (like 7), strings (like "I have a dream"), characters, nil, booleans, keywords, symbolic values (##Inf (∞), ##-Inf (-∞), and ##NaN (Not a Number)), collections (lists, vectors, maps, and sets), and records (deftype and defrecord).

Tagged Literals

Example 1 - #uuid

Users can add their own custom literals to the list above with a tag. For example, Clojure version 1.4 shipped with built-in tagged literals for #uuidA UUID is a Universally Unique IDdentifier. It denotes an ID that is so rare that the chance of another computer coming up with the same identifier is nearly zero. The type is not natively supported in Clojure, but the #uuid tagged literal adds this functionality.

and #instantAn instant is an object in Java that represents a single point in time.

.

Evaluating the string "efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907" prefixed with #uuid generates a java.util.UUID type:

#uuid "efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907"⇒ [java.util.UUID, "0x785d0e2f", "efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907"]

Clojure reads the literal string first, "efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907", and then invokes the tagged literal function on the string. In this example, #uuid dispatches java.util.UUID/fromString on "efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907".

The generic string is now a meaningful bit of data; "efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907" is not the same as "#uuid efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907".

(= "efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907"

(java.util.UUID/fromString "efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907"))⇒ false

The two strings of characters are not equivalent because the first one is not of a UUID type. Adding #uuid makes it so:

(= #uuid "efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907"

(java.util.UUID/fromString "efea38cd-0db8-4f66-b3ab-c50b4c08d907"))⇒ true

Conversely, #uuid cannot prefix a string that is not a valid UUID:

(try

(java.util.UUID/fromString "not-a-uuid") ;; #uuid "not-a-uuid"

(catch IllegalArgumentException e (.getMessage e)))⇒ "Invalid UUID string: not-a-uuid"

Tagged literals are succinct and easily read by humans, making them a perfect fit for structured data. They are the extensible part of the extensible data notation (edn) I’ll be using to store time and date values.edn was covered in Part 1. It is a structured format for conveying values, often used where one might use JSON. More at the official edn readme.

Example 2 - #inst aka Joda Time

Tag a well formatted date string (i.e. something that looks like a date) with #inst to generate a java.util.Date object:

(type #inst "2020-05-11")⇒ java.util.Date

If the tagged literal is stored as a string, it will automatically be read as a java.util.Date object when read using clojure.edn:

(clojure.edn/read-string "#inst \"2020-05-11\"")

⇒ #inst "2020-05-11T00:00:00.000Z"Two notes on this result. First, T00:00:00.000Z is the timestamp for this date, automatically added by the system. Second, the string that generated this result, "#inst \"2020-05-11\"", uses the backslash (\) to differentiate the quotes that are part of the string from those which denote the string itself. This is known as an escape character.

It is now possible to operate on the date and time information: add days, find the difference between two dates, display the day of the week, display the year, etc….

(import '(java.text SimpleDateFormat))

;; Grab the year

(->> (prn-str #inst "2020-05-11")

(clojure.edn/read-string)

(.format (SimpleDateFormat. "yyyy")))⇒ "2020"

But there is a big problem! I don’t want to work with java.util.Date, Java’s legacy date type. Joda Time’s official site suggests that people use Java Time.“Joda-Time is the de facto standard date and time library for Java prior to Java SE 8. Users are now asked to migrate to java.time (JSR-310).” (“Joda-Time - Home”, joda.org, 2020.)

So rather than working with built-in #inst tags, the rest of this demonstration will use #time/date tags as part of cljc.java-time - an excellent library for working with Java Time in Clojure.

time-literals

Here’s how cljc.java-time was used in Part 1:

(require '[cljc.java-time.local-date :as ld])

(ld/now)⇒ [java.time.LocalDate, "0x61da6671", "2020-07-12"]

With time-literals, I can prefix #time/date to my string and work with it as a Java Time LocalDate.

(require '[time-literals.read-write :as time-read])

(def time-date-string (time-read/print-date "2015-12-11"))

time-date-string⇒ "#time/date "2015-12-11""

Using the edn/read-string function with the #time/date tag is almost identical to using it with #inst. Only now I must supply clojure.edn/read-string with a reader that can interpret the custom #time/date literal: {:readers time-read-prn/tags}.

(clojure.edn/read-string {:readers time-read/tags} time-date-string)⇒ [java.time.LocalDate, "0x3d6a5fc1", "2015-12-11"]

Now it’s possible to read a string, "2015-12-11", add 90 days, format the date, and generate the result, March 10, 2016:

(require '[cljc.java-time.format.date-time-formatter :as formatter])

(-> (clojure.edn/read-string {:readers time-read/tags} time-date-string)

(ld/plus-days 90)

(ld/format (formatter/of-pattern "MMMM dd, yyyy")))⇒ "March 10, 2016"

Displaying the year from any tagged literal date is simple:

(->> "#time/date \"2011-01-01\""

(clojure.edn/read-string {:readers time-read/tags})

(ld/get-year))⇒ 2011

Curriculum Vitae

Now to apply this time/date software to solve my original problem: recording events in my professional life in a way that is 1. easy to write and read and 2. easy to format programmatically.

Peruse any of the .edn files in my repository to see how my professional data is structured. Here are two examples:

A public speaking engagement:

{:org "Curry On"

:geo "London, UK"

:date #time/date "2019-07-15"

:title "Say What You Mean"

:subtitle "Exploring Declarative Computation in Art"

:link "https://www.curry-on.org/2019/sessions/say-what-you-mean-exploring-declarative-computation-in-art.html"

...}An employer:

{:org "Stevens Institute of Technology"

:title "Adjunct Professor"

:desc "College of Arts and Letters"

:geo "Hoboken, NJ, US"

:date-bgn #time/year-month "2017-01"

:date-end #time/year-month "2019-05"

...}Take note of the dates. They are easy to read and consistent. I’m interested in the specific day I gave a talk and the span of time I worked at an institution. Adding a time to my presentation or a day to my employment would be trivial if I had that information.

The extensible .edn reader makes it easy to ingest this data and format it programmatically for any destination. Look at my CV and see the various ways dates are displayed. In general, I try to record timestamps with as much specificity as possible and then worry about how it’s formatted later.

The code that generated the CV is in the same repository, but here is a small excerpt that takes a vector of organizations and extracts several elements to display. Specifically:

- The organization’s name:

:org - The organization’s geographical location:

:geo - My status in the organization:

:title - The the date(s) I was a member of the organization. The conditional

ifstatement displays the date depending on whether I was a member for a single year or over a span of time.

(let [affiliations (second x)]

(into [:div ] (map #(edn->hiccup (:org %) (:geo %) (:title %)

(if (:date-bgn %)

(java-time->str (:date-bgn %) (:date-end %))

(java-time->str (:date %)))) affiliations)))Each entry is placed into an html-like structure for display on this website.

Archiving Time

A final note on recording time in digital records. Even the most widely used systems are prone to pitfalls. Robert Jansma explores common problems in his forthcoming master’s thesis, Scoops and Brushes for Software Archaeology: Metadata Dating.

Jansma developed a metadata dating tool that helps researchers discover trends in a program’s use and development. In his thesis, Jansma applies his software to the growth and decline of De Digitale Stad, a 1990s Dutch “digital city.” His software leverages four types of time-related metadata that appear in many Unix systems: birth time, ATime, MTime and CTime. These fields are not traditional date records centered on the birth of Christ, rather they are seconds since the Unix epoch, traditionally 1970-01-01 00:00:00.

Sounds simple enough, but as we have seen, nothing is simple in time.

- Birth time: time when the file was created. The presence of birth time depends on the filesystem, not the operating system. For example, MacOS’ APFS and HSF+ both allow for birth time. Birth time is also present in Ubuntu’s ext4, but Ubuntu itself does not fully utilize the field.

- Access time (ATime): then when a file was last accessed (but not necessarily modified). Sorting files by ATime can reveal how a system is used. For example, Jansma mentions that ATime can be used to recreate the final steps taken on a system before it was permanently shut down.

- Modify time (MTime): time when a file’s content was last updated.

- Change time (CTime): time when a file’s content, or its metadata, was updated. Changes to a file’s permissions or a name change will alter the CTime but not the MTime. Jansma suggests that insights can be gained when MTime and CTime are different.

Inconsistencies often arise in each time stamp’s implementation, so comparing different operating systems and file systems can be difficult. But this is the nature of time. It is hard to measure - sometimes it flies by, other times each second is an agonizing tick on the clock - and impossible to grasp.There is a term for this in Buddhism: shunyata. It is often translated as “emptiness”, but as Mu Soeng suggests in The Heart of the Universe: Exploring the Heart Sutra, it may more accurately be understood as “momentariness” or “transitoriness” (Soeng 42). Moments are the true units of time. They are full of everything that gives life meaning while forever fleeting due to their inherent emptiness.