Red Sunset on the Dnieper by Arkhip Ivanovich Kuindzhi (1905–8) The Dnieper river connects Russia and Ukraine. It originates west of Moscow, runs through Kyiv, and pours into the Black Sea.

Red Sunset on the Dnieper by Arkhip Ivanovich Kuindzhi (1905–8) The Dnieper river connects Russia and Ukraine. It originates west of Moscow, runs through Kyiv, and pours into the Black Sea.Russia has been at continuous war with Ukraine since 2014.An Italian version of this essay was also published by the magazine Q Code as La guerra dell’informazione è senza limiti (e senza limiti sono le conseguenze).

The years between Russia’s initial invasion in Crimea and yesterday’s expansion were filled with relentless cyberwarfare. These attacks have inflicted suffering far beyond the boundaries of the network. Much like the Stuxnet virus deployed by Israel and the United States in Iran, these attacks cause physical harm and in the case of Russia’s incursion, have resulted in the deaths of innocent Ukrainians.

Russia’s actions are inline with the Makarov/Gerasimov approach to conflict. Valery Gerasimov, the chief of the general staff of the Russian Federation armed forces, described warfare as a spectrum of theaters in 2013. The theaters extend beyond land, sea, and air. They include terror, propaganda, economic coercion, and cyberwarfare.

Other hegemonic nations undoubtedly deploy similar tactics. But Russia’s strategy is not only explicit, it is time-tested. Here is Yuri Alexandrovich Bezmenov, a former KGB agent and defector, describing similar Soviet tactics in 1984.

Taking the attack on Ukraine as an eight year conflict illustrates the current state of warfare. No pre-internet technology ever allowed such unabated aggression across national borders. It is unclear how nations can and should respond to this aggression.

The essence of information warfare makes the conditions of fighting wars even worse. Information warfare intentionally amplifies the background noise of misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation. This is not only a tremendous barrier for peace, it is the foundation of disaster.The Moscow–Washington hotline embodies the need for clear communication between nuclear-armed states. Established in 1963, the hotline remains text-only as a way to reduce misunderstandings in communication.  Moscow-Washington teletype hotline, Jim Kuhn

Moscow-Washington teletype hotline, Jim Kuhn

A quick survey of the last eight years will help illustrate my point.

February 2014: Ukrainian Revolution

Viktor Yanukovych was swept out of power on February 22, 2014 after a months-long protest turned violent earlier that month.Paul Manafort was a political consultant for Yanukovych’s pro-Russian Party of Regions starting in 2006. He worked in Ukraine until Yanukovych’s ouster. He would later reappear as Donald Trump’s campaign chair in 2016. Manafort is an international war profiteer, American lobbyist, and professional opportunist. His involvement in any enterprise should always raise a red flag.

The parliament’s vote to impeach on the 22nd is considered a coup by the Russians.This claim is bolstered by demonstrable American meddling in Ukraine’s politics leading up to the election.

Western interests were sharply divided at the time. As I detailed in my post Disinformation Strategies and Tactics (2020), Russia made several attempts to exploit this division:

On February 4, 2014, an anonymous source posted a private conversation between the US Assistant Secretary of State, Victoria Nuland, and the US Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt. Amidst all the political banter, one line stood out, “Fuck the EU.”

The leaked audio was a crude effort to sow dissension between the US and its EU allies during a tense moment in Ukraine - a move that would clearly help Russian interests. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, meddling in the US elections, and the dissemination of NotPetya [computer virus] made the nation an exemplar in hybrid information warfare.

March 2014: Russia Annexes Crimea

Russia annexes Crimea weeks after the impeachment. “Little green men” who took the peninsula wore no Russian markings but carried Russian weapons.Little green men.  Credit: Elizabeth Arrott/VOA - Voice of America

Credit: Elizabeth Arrott/VOA - Voice of America

The Kremlin farcically denied involvement.

As Russia used official channels for denials, fictional online personas were created online to stoke ethnic fears within Ukraine. Russia hoped that national infighting would sow the seeds of paranoia and distrust before the May 2014 elections.

May 2014: Free Ukrainian Elections

Without a viable candidate to back in the presidential race, the Russians sought to amplify the chaos they had created in Crimea.

Ethnic divisions, dubious reports, and salacious rumors were planted online. On the day of the election, hackers wiped data in voting systems. Hackers also co-opted the systems that reported the vote tallies. News reports declared that Dmytro Yarosh, leader of the ultra-nationalist Right Sector Party, was ahead in the count.

Petro Poroshenko ultimately emerged victorious after the Ukrainians were able to restore order. He garnered 54% of the vote. Yarosh would fail to even net 1%.

Gen. Philip Breedlove (NATO) called the actions of early 2014 “The most amazing information warfare blitzkrieg we have ever seen in the history of information warfare.”Sanger, David E. The Perfect Weapon: War, Sabotage, and Fear in the Cyber Age. First paperback edition, Broadway Books, 2019.

But Russia was not finished.

2015/2016: The Ukrainian Power Grid

In the winter of 2015, an orchestrated attack on Ukraine’s electrical grid cut the power for hundreds of thousands of people. The attackers made it difficult to solve the issue by disabling internal monitoring systems and overwhelming each provider’s call centers so legitimate callers could not get through. This took place after pro-Ukrainian activists physically attacked a substation that powered Crimea.

It’s conceivable that the physical attack on the substation prompted the cyberattack as a response. Which begs the question, when will a cyberattack become a pretense for a physical response? And at what scale?

2017: NotPetya

The Russians successfully attacked the electrical grid again in 2016. But it was the next salvo that demanded the world’s attention.

The NotPetya malware first appeared on the eve of Ukrainian Constitution Day. As I chronicled in Disinformation Strategies and Tactics, NotPetya’s blast radius extended far beyond Ukraine’s borders. It affected thousands of systems in over 65 countries.Russia was one of those 65 countries.

Maersk, a single Danish shipping company, lost $300 million in revenues and was forced to replace 4,000 servers.

The attack cost billions of dollars to mitigate.The United States, United Kingdom, and Australia official attributed the source of NotPetya to Russia in February 2018. The lag between attack and attribution conveys the difficulty of collecting sensitive forensic evidence and presenting a compelling case.

But Ukraine suffered most of the damage. The malware’s intended target netted 80% of all infections.

2020/2021: The Ongoing Front

Cyberattacks continued to bombard Ukraine at the turn of the decade. Ukrainian officials reported 397,000 cyberattacks in 2020 and over 288,000 cyberattacks in 2021. It cannot be said that every one of these attacks are Russian in origin, some may be perpetrated by the same little green men that invaded Crimea.

January/February 2022: Expanding the Invasion

Unhappy with simply occupying Ukrainian Crimea, the Russian military encircled Ukraine in early 2022. A series of cyberattacks swept through Ukraine as the Russians took position.

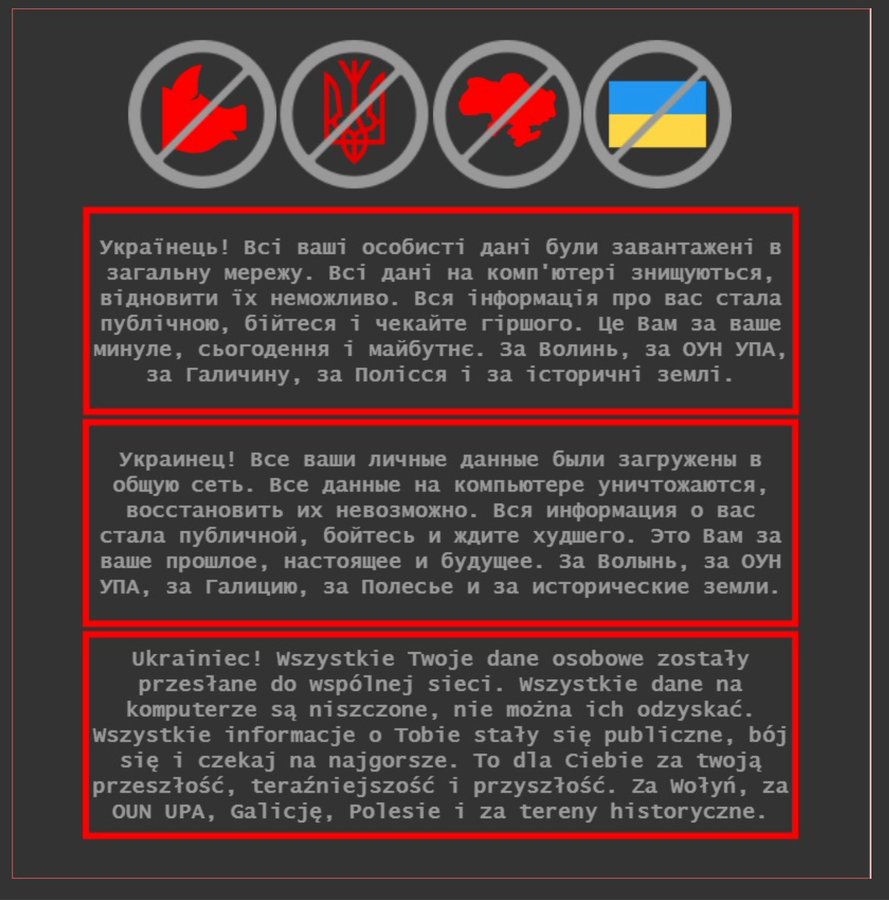

In January, hackers took down took down the defense, foreign, and culture ministry websites. The two largest state banks in Ukraine were also taken offline. The websites were replaced by an ominous message, “Ukrainians!…All information about you has become public, be afraid and expect worse.”

MFA Ukraine website via Christopher Miller

MFA Ukraine website via Christopher Miller

A data wiping malware called HermeticWiper was deployed a month later - on the same day Russia officially recognized the separatist regions in eastern Ukraine.

The direct consequences of these cyberattacks are not yet known. Russia attacked Kiev the next day and the world has been preoccupied ever since.

Going Nuclear

The Cold War is littered with nearly-nuclear confrontations. As you consider this selection from Close Calls with Nuclear Weapons by the Union of Concerned Scientists, know that each incident prompted the scrambling of bombers and placing intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) crews on the highest alert.

- October 5, 1960: The U.S. early warning radar at Thule, Greenland […] detected dozens of Soviet missiles launched against the United States.

- October 28, 1962: Just before 9:00 am, radar operators at Moorestown, NJ, reported […] that a nuclear attack was under way, with impact expected at 9:02 near Tampa, FL.

- November 9, 1979: Computers at NORAD headquarters indicated a large-scale Soviet attack on the United States. […] Investigations later discovered that the incident was caused by a technician who had mistakenly inserted a training tape containing a scenario for a large-scale nuclear attack into an operational computer.

- March 15, 1980: The Soviet Union launched four submarine-based missiles […], one of the launches appeared to have a trajectory aimed at the United States.

- September 26, 1983: A Soviet early warning satellite showed that the United States had launched five land-based missiles at the Soviet Union.

There are many more. And the culprit for each of these nuclear near-misses was simple misinformation.

In the years since the Cold War, the internet has flooded the world with information. Information warfare seeks to take this theater of conflict and amplify the amount of misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation. Those of us who work in the information space must recognize our place in this reality.Cryptocurrencies power a $5.2B/year ransomware industry and help enable rogue states. Any serious Web3 efforts to serve individual sovereignty need to address these issues head on.

The Nuclear Age Meets the Information Age

Technologists must abandon the notion that technology is neutral. It is the first step towards building a better internet.

Many advanced technologies have inextricable political dimensions. Both nuclear power and nuclear weapons enforce central and hierarchical political structures. This was evident when Ukraine inherited the third-largest nuclear arsenal after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Ukraine gave up their nuclear weapons in 1994 in exchange for assurances by the United States of America, the Russian Federation, and the United Kingdom that their security and sovereignty would be maintained. This agreement was known as the Budapest Memorandum.

It’s easy to argue in 2022 that Ukraine made a tremendous mistake when it agreed to the Budapest Memorandum. Nuclear weapons are real and assurances are not. But that’s the key - nuclear weapons are real and they enforce a real and non-negotiable political order. As long as your nation has nuclear weapons, you will have a political class of people that must maintain them. This class might look different in Russia, France, Pakistan, and the United States, but it is only a matter of degrees.

This class of folks are essentially autocrats. They must be heard. They must be organized around. Other weapons can exist in more distributed or chaotic systems. But not nuclear weapons. Their destructive power is too great. This is the inherently centralizing force of nuclear technology.

If your nation aspires to a political system without a trace of autocracy, removing nuclear technology is the only choice. That’s the radical vision the Ukrainians embraced in 1994; they remain one of the few nuclear nations to ever give up their armaments.

As Ukraine attempted to shed its 20th century legacy, the country was sucked into a 21st century conflict; most of the fighting over the last eight years of the Russo-Ukraine War has happened in cyberspace.This parallels the Estonian push into cyberspace. Partially due to the geopolitical tensions of being an ex-Soviet state, Estonia created an advanced e-state and become a leader in cybersecurity.

The attacks have only intensified since the start of the 2022 invasion. The release of malwares in Ukraine such as Foxblade and HermeticWiper seemed to intentionally coincide with the initial onslaught. Since then, at least 100 additional malware deployments have been detected across a variety of Ukrainian industries. This includes at least two additional cyberattacks on Ukraine’s power grid.The malware used in 2022 was a variation of the malware used in the 2016 power grid attack. The original was called Industroyer and the 2022 version was deemed Industroyer2.

The news outlet KyivPost reports “constant cyberattacks” as government websites have struggled to stay online.

Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukrainian deputy minister and minister for digital transformation, has launched an online hacker recruitment effort in response. The official Telegram group has swelled to more than 280,000 volunteers and the initiative has organized an array of defensive and offensive missions.

Independent hacking groups have also initiated a handful of attacks within Russia and Belarus. Notable among the subsequent bank leaks and train shutdowns, Anonymous took control of several Russian television channels like Russia 24, Channel One, and Moscow 24 to broadcast footage of the war in Ukraine.

War is chaotic and cyberwar intensifies the chaos. The combatants can come from anywhere while a cyberweapon’s origin and blast radius is indeterminate. Like a nuclear bomb, the fallout from conflict can easily spread across national borders and stoke global hostilities.

Technologists must help politicians and society-at-large understand what is at stake. The first step is acknowledging the politics embedded within our technologies.For example, a myopic Web3 that only seeks to recreate capitalist constructions in cyberspace will only recreate today’s issues in a different form.

If we hope to clearly express our intentions, we must understand the medium through which they travel. And if our intention is a lasting peace, we must eliminate the tools of autocratic power.

The final five paragraphs of this entry was updated on 23/April/2022 to better reflect the ongoing war in Ukraine.