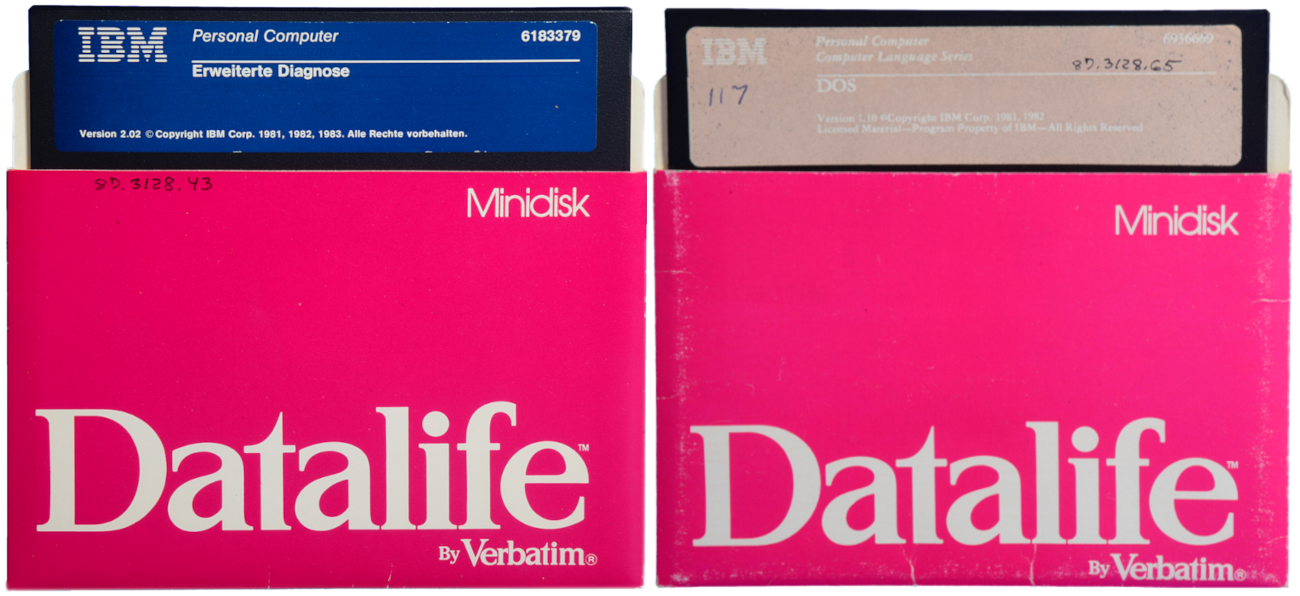

Software, Erweiterte Diagnose, Software, IBM DOS Version 1.10

Software, Erweiterte Diagnose, Software, IBM DOS Version 1.10

What if “data” is a really bad idea?

Several years ago, esteemed computer scientist Alan Kay participated in an Ask Me Anything on Hacker News. Kay always sparks interesting conversation and I was happy to see Rich Hickey, a practitioner held in equally high regard, join the thread. The dialogue was kicked off by Kay’s provocative musing on the legitimacy of data; not just some data, but the idea of data itself.Kay has made a career out of challenging conventional wisdom. Perhaps this is best embodied by one of his most famous quotes, “A shift in perspective is worth 80 IQ points.”  Alan Kay by Jean Baptiste

Alan Kay by Jean Baptiste

It was a bit like a physicist asking, “What if gravity is a bad idea?”

Kay and Hickey largely talked past each other and never really got to engage the question. But I think it’s one worth exploring. Not only in the technical dimensions of data, but also in the inescapable political dimensions of its automation.

Data Is an Objectifying Force

Data is inherently objectifying. This property is an asset when describing inert phenomenon such as the composition of soil or the properties of various metals. Data enables the applied work of engineers and there are no direct ethical considerations.There are plenty of systemic ethical considerations when using these resources. But that’s beyond the scope of this article.

The problems become apparent when we start talking about people. Data cannot express a meaningful distinction between intelligent actors and the things they act upon; a database that tracks widget production can also store information about the people who buy those widgets. Databases then turn intelligent actors - who are often human beings - into things to be acted upon. This is where data can quickly become a “bad idea.”

Kay was likely gesturing to a different reason data might be a bad idea. I’ll address that in a moment. But encoding human identity in a database can lead to real-world tensions and consequences, such as the March 27, 1943 bombing of the Amsterdam Population Registry.Orchestrated by Dutch resistance members, including Willem Arondéus, Gerrit van der Veen, and Dr. Frieda Belinfante, their goal was to inhibit the Nazi’s ability to track and deport Jews and other targets of terror. The operation managed to destroy over 15% of the records. Many of the participants were later captured and executed by the Nazis. Noted privacy advocate and lawyer Lau Mazirel was also a member of the Dutch resistance.  Lau Mazirel (1907-1974) Collectie Van Gennep / IISG

Lau Mazirel (1907-1974) Collectie Van Gennep / IISG

So it’s something we can examine to gain a better understanding about why this issue matters so much.

Amsterdam public registry (March 28, 1943) Amsterdam City Archives

Amsterdam public registry (March 28, 1943) Amsterdam City Archives

Data Is a Centrifugal Force

Data processing is the lifeblood of large bureaucracies. As previously discussed in the article Personal Privacy, efforts to mitigate the reach of data collection in democratic nations goes back decades. Consent is the latest fashion. It’s the idea that drives those cookie popups on websites; a person is granted agency every time they make a choice about which cookies are placed on their machine.

Most people find these popups annoying. We don’t want to negotiate every time we encounter a new website. We’re used to social structures where consent is provided implicitly. A look of the eye and unspoken social contracts are the norm. But data is too brittle to capture this kind of nuance.

Alan Kay took note of how everything from simple organisms to complex societies negotiate in novel situations. It lead him to propose an abstract concept of ambassadorsAlan Kay was originally thinking about objects interacting on a network. Currently, all network interactions follow explicit protocols. Objects of the future, Kay believes, must be able to negotiate the exchange of data even if they come from completely unknown sources. As Kay noted in the conversation with Hickey, “For important negotiations we don’t send telegrams, we send ambassadors.”

in computer science. Ambassadors might like to follow a protocol, but it isn’t required. They act on behalf of a larger autonomous entity. And when two ambassadors meet, both entities they represent retain their autonomy.

How could data be this flexible? How could data bring the requisite context along for the ride?Usually data relies on the medium to provide context. The medium is the protocol. For example, I could send you data through a perfect medium with perfect fidelity and you may still receive it as noise unless you know how to interpret it.

This is probably what Kay was thinking about with his Hacker News prompt.

Efforts to implement ambassadors haven’t gotten very far. Data still seems to work best in aggregate. It continues to be sucked into the private warehouses of powerful organizations, further entrenching their power. This centrifugal force is political in nature. As a political arrangement it can be countered by a variety of approaches - from law (new regulations, license enforcement, etc…) to systemic changes and technological obsolescence.

Rather than chase after this hazy idea of an ambassador, I’ll spend the rest of this post exploring concrete ways to expand our notion of data. I’ll specifically work with the idea of using data to represent human identity. I will focus on data delivery over the ubiquitous HTTP protocol using the client/server model. Lots of interesting work is happening on peer-to-peer protocols, but I’ve found much of the last ~10 years of venture-backed, market-centric crypto solutions to be misguided.Most so-called Web3 efforts attempt to graft a marketplace on top of data to decentralize this power structure. But none respond to tendency of marketplaces themselves to consolidate power. Combined with the political dimension of raw data and the proven power of network effects, this can only lead to an incredible consolidation of power. Thus for those who are not in power, data will seem like a bad idea.

This is an examination of what it would take to build a more human-centric arrangement by going back to the fundamentals of data - where it lives, how it moves, and what it means.

Data and Identity

Identity is a natural place to start when talking about people. The following discussion is based on two observations: 1) data naturally reduces complex conceptions of identity into coarse representations and 2) data about identity is generally held in systems far away from the people they identify.I’m also going to avoid discussing self-sovereign identity directly even though I invoke several technologies associated with the effort.

The second point is a result of the centrifugal force of data. We can resist this inertia by changing the physical characteristics of data - from “far” (in your warehouse) to “near” (in my hand) and from “dead” (jealously hoarded on private property) to “living” (flowing through the commons). Such data could exhibit different political dimensions and become more expressive.

Philip Agre enumerated five characteristics of data that will help us achieve this repositioning. Agre argued that “living data” must be able to express 1. a sense of ownership, 2. error bars, 3. sensitivity, 4. dependency, and 5. semantics. Although he originally wrote this in the early 1990s,Phil Agre. “Living Data.” Wired, November 1, 1994.

it took some time for technology and policy to catch up. I’m going to break down each point using more contemporary context and terminology:

- Provenance and Agency: what is the origin of the data and what can I do with it (ownership)?

- Accuracy: has the data been validated? If not, what is the confidence of its correctness (error bars)?

- Data Flow: how is data discovered, updated, and shared (sensitivity to changes)?

- Auditability: what data and processes were used to generate this data (dependencies)?

- Semantics: what does this data represent?

Each one of these could constitute its own blog post. Their viability today is due to a confluence of cultural priorities, technologies, and policy. I’ll mostly gesture towards the specific technologies. Follow the hyperlinks if you want to know more.

1. Provenance and Agency

Where did this data come from?

Initiatives such as Verifiable Credentials (VC) and the Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI) both provide certain guarantees about the veracity of data. VCs are data that can be verified by the original issuer. CAI is supported by companies like AdobeAdobe’s existing Digital Rights Management (DRM) is used to treat customers who buy books like criminals. Furthermore, when the company purchased Flash (via Macromedia), they inherited an ecosystem that sustained countless digital cultural artifacts. When they discontinued the technology, the only responsible step would have been to subsequently open-source the entire project so these artifacts could be maintained. Adobe has failed to demonstrate vision or leadership when dealing with cultural issues so I’m skeptical of CAI.

because they’re looking to provide provenance and attribution for rich media.

Verifiability and ownership can undoubtedly be useful. But ownership is a slippery slope. Many futurists, especially those in Web3, want to apply property rights to aspects of our identity. Any attempts to commodify self-hood is an egregious misapplication of technology. Not only is it ethically dubious, it’s technologically incoherent. As health technologist Adrian Gropper points out, “control doesn’t scale.” Individuals simply do not have the time or expertise to manage a portfolio of online personas or a single persona that discloses only essential information to a portfolio of clients.

For example, we have “ownership” over the organs in our body, but we thankfully don’t have conscious control over their management. If we did, we would need to outsource the burden of “personal organ management” to an outside entity to get anything else done.

What are we allowed to do with it?

Permissions are a time-tested way to express property rights. In computing, they have been around as long as multi-user operating systems. Cloud filesystems like Dropbox and Google Docs have made these coarse permissions an everyday affair.The ubiquitous Google Sheets permissions error:

A website’s non-negotiable Terms of Service is also a set of permissions. They dictate what a website is allowed to do with a person’s data and they also dictate what a person is allowed to do with the data once it’s in the system. This power imbalance stems from the fact that 1. the website holds both the means of computation and the data to compute and 2. a person using a website often has neither.

But technologists are attempting to build infrastructure that separates these two concerns: application (the means of computation) and data. Adoption of either Solid or local-first software principles would change the power dynamic between large software vendors and individual people. Solid even offers a specific open standard for application interoperabilitySolid supports RDF, which offers an open way to link data. The web-wide aspirations for linked data have fallen short, but RDF is used successfully in many important projects.

while a person’s data remains on their personal filestore.Solid organizes personal information using a hierarchical filesystem. RDF can be used to structure information within files, enabling direct manipulation of data while also supporting data validation and complex queries. It’s a bit of a mixed metaphor that needs more work. But I suppose there is a precedence of file-based databases going back to the 1980s, like dBase III.

These options do not address Gropper’s axiom that “control doesn’t scale.” It’s likely that any practical solution will require a separation between the computation service, the data store, and the user interface. This third column would allow expert administration of certain personal data.Expert administration could also be a personal AI that lives on a person’s local device. Or it could be a data collective that provides sophisticated management.

2. Accuracy

How reliable is this data?

There are a myriad of private “Know Your Customer” (KYC) solutions that help ensure that identity information is accurate. I’m going to eschew these closed-sourced solutions that exist to silo data in hopes to extract rent or transaction fees in the future.

I’ll instead circle back to Verifiable Credentials because they provide a “triangle of trust” to ensure accuracy over open protocols. Do I really trust that he earned a degree at that university? Don’t take his word for it, check the claim with the university.

The trust relationship makes VCs an elegant solution without data lock-in. Any accredited claim can be checked. But remember, behind each claim is a bureaucracy to administer it. Herein lies the practical danger of VCs. Making credential checks easy ensures that we will have more of them. Which means more bureaucrats. It’s a road we must build cautiously.Corey Pein would argue that this is the logical outcome of Computer Science as a discipline. It is a “fake science” that is created by and for bureaucrats. From Baffler #38: “No, the plodding, characteristic precepts of software design mainly serve to ratify the status quo drudgery of bureaucratic servitude—and indeed to elevate it into a theory of crudely incentivized mass deference. Strip away the nomenclature of cybernetic systems theory and software design, and you have something very close to the plot prospectus for a Philip K. Dick novel.”

3. Data Flow

How fast does the final answer change as you start modifying the input by plausible amounts?

Think of the familiar spreadsheet where data flows through a set of cells to calculate an answer. For this to work, the data must have meaningful semantics. “3 more than 29” is 32. But “3 more days from January 29” is February 1. The semantics make two cells or two computers interoperable. Anything short of these clear semantics would require one of Alan Kay’s hypothetical ambassadors.

All data in the flow must also have a name so it can be found. And resilient software would need a contingency plan in the event that data changes its name or goes missing. These requirements are difficult to deliver on a networked system.

VCs support updates because the state of the credential is subject to change. But they are named using the same Domain Name System (DNS) as the Web; we have all experienced link rot and know that there is a lot left to be desired.

There is also a way to discover the name of a VC even if you don’t know it through the .well-known convention. Solid doesn’t offer the same benefits, but changes to linked data can theoretically propagate. And Solid folks are working on a Webhook (v 0.2.0) standard to serve updates to linked data over REST.

There are many efforts to chip away at this issue: Decentralized identifiers (DIDs) to resolve the naming issue, conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs) to resolve file changes, content address storage on IPFS as a way to ensure data integrity by making it immutable. These are just a few of the promising technologies, but nothing has emerged as a comprehensive solution to this problem.

4. Errors: Integrity and Reproducibility

Errors propagate a lot faster than they can be repaired. […] If something is screwy, can we trace the calculation back and figure out which input it depends on?

This problem is related to Data Flow. At first glance, it may make sense to combine the two sections. But focusing exclusively on errors foregrounds another way to handle data: immutability.

Immutability simply means that data can never change. The most famous implementation of an immutable database in the last twenty years is the blockchain. Both errors and fraud can be audited for correctness because an entire immutable history exists.

This tamper-evident property is shared by VCs. And a fraudulent University degree can be revoked just as easily as an expired certificate.

Solid does not work with immutable data, but folks are working on similar guarantees through a Solid non-repudiation service.

Popular tech offerings like Dropbox and Google Docs store a record of changes to a shared text file. But this form of version control wasn’t really designed for an automated audit.

There are many ways to approach this problem. While blockchain technologies owned the hype cycle a few years ago, leveraging their benefits can be challenging and their slow transaction speeds cause their own problems. So just like Data Flow, the best solution has yet to surface.

5. Semantics

It’s very common for two databases to contain columns of data named by the same word - such as “price” or “name” or “approved” - even though that word means subtly different things to the people who created the databases.

This issue is the culmination of all the others. Information has to be meaningful if it going to be shared and processed. File system metaphors like Dropbox and Web Native File System use file extensions and MIME types to understand what they are working with. Solid’s RDF support provides even more semantic detail than files. Narrowly defined protocols like OpenID Connect make it possible (and common) to share basic identity information using scopes.

Semantics have a major drawback: they have to be widely agreed upon. Widely-adopted semantic vocabularies are usually refined by a small group of experts until a rough consensus is reached. This approach can be seen in contra-distinction to tags. Tags also provide meaning to data, but they are formed organically by a large group of people generating a large number of tags; tagging trends then emerge over time and provide context for information.

These tags can lose their meaning in different cultural contexts or on different platforms - the #meta tag might imply something different on Flicker versus its use on Facebook. But machine learning has flattened these differences. Algorithms can now identify similar data across the internet with or without tags or vocabularies.The black box nature of machine learning is particularly insidious here. Every solution has implicit biases, but machine learning offers none of the transparency afforded to other methods for structuring and describing information.

Control Does Not Scale

It’s not possible nor desirable to provide each person a simulacrum of their identity online. People don’t want to manage their own data any more than they want to run their own servers. But large data centers are political artifacts‘Conventional wisdom posits technology as a neutral force that can be wielded for “evil” or for “good.” But as Langdon Winner has pointed out, technologies can fundamentally embody explicit political arrangements.’ ~ How the Consumer Computer is Consuming Computing.

that necessitate both political and technological responses. This response depends on how we situate identity data in our lives. Data is ideally close to home, separate from the processes that compute it. But it is often far away and embedded in the software we use.

Resituating data is easier said than done. Data must have some sense of authenticity to be useful, it must have some contextual meaning to be shared, and it must leave room for error if it is to be alive. Agre’s principles are clear but the road to implementation is not.There are many solutions not described in this article. Philip Agre mentions an ill-fated “intelligent agent” solution from the 1990s called Telescript. Indeed, there are folks who are working on agent solutions today. Their focus on intention rather than data may even be closer to Kay’s ambassadors.

Any real political response will require more than introducing new tech. For example, consider all the institutional support needed to manage a currency in your country. And then remember that a person’s identity is infinitely more complex than any financial abstraction.

It may seem insurmountable, but the alternative is a single dominate political vision where only one form of data management exists: large data centers filled with coarse data points and countless assumptions about what that data says about who we are. This is indeed a bad idea.